Reprint:

![]()

Germ Warfare

The Sunday Times Magazine

May 17 1998

By Brian Deer

Matthew Bell lay on the sofa in the front room of his home and snuggled against a cushion half as big as himself as he gazed at Batman Forever on video. He was crazy about superheroes in serious outfits – Batman, Spiderman, Fireman Sam – and cut quite a figure himself as a blond-haired Superman at his local toddlers’ group in Torrisholme, Morecambe. But on this Monday afternoon – it was nearly 4pm – his attention to the movie faltered. He had started to feel odd sometime earlier in the day, and now he had a pain in his tummy. Matthew grasped the cushion in a vain search for comfort, and wished the hurting would go away.

His mother, Rachael, was in the kitchen next door, grilling fish fingers for tea. As she laid out three plates, her youngest son, Tom, trotted between the rooms. It had been an exhausting day, like every day for this lone mother with two small children. On Friday, they had been for milkshakes at Brucciani ice cream parlour on the Morecambe promenade. On Saturday, Stuart, the boys’ father, a painter and decorator, had come over and taken them all to McDonald’s. Yesterday, they had played at a sea-front sandpit. And today they picked apples at an allotment. When Matthew complained, “Mam, my belly hurts,” it seemed like just another routine stress.

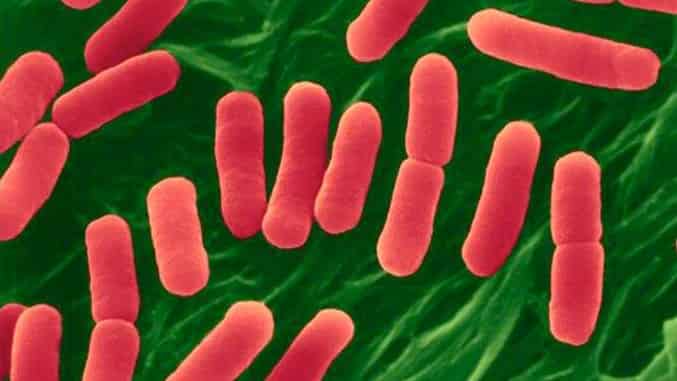

Had Rachael known then what she found out later, she would have been terrified. Matthew, three years and nine months old, was showing the first symptoms of infection with the same kind of E-coli organism that is currently the subject of an inquiry in Scotland, after an outbreak in November 1996 traced to a Lanarkshire butcher’s shop killed 21 people. As that Monday afternoon turned to evening, vicious toxins produced by the bug stuck to and attacked her child’s gut. He started to suffer from diarrhoea and agonising stomach cramps. And he would soon become seriously ill.

A full explanation of what was happening to Matthew is still beyond medical science. The particular variety of the Escherichia coli bug that he had picked up – called O157:H7 – is a freak mutation of a normally harmless germ, and only surfaced in the 1980s. Despite a string of devastating outbreaks around the world, it never used to be thought to be a big enough threat to be worthy of major research. But last year the number of laboratory-confirmed infections in Britain suddenly jumped by 80%, to more than 1,500 cases, and experts are now alarmed. “It may have peaked,” says Hugh Pennington, professor of bacteriology at Aberdeen University and the government’s chief adviser on the subject. “But it may get 10 times worse.”

A full explanation of what was happening to Matthew is still beyond medical science. The particular variety of the Escherichia coli bug that he had picked up – called O157:H7 – is a freak mutation of a normally harmless germ, and only surfaced in the 1980s. Despite a string of devastating outbreaks around the world, it never used to be thought to be a big enough threat to be worthy of major research. But last year the number of laboratory-confirmed infections in Britain suddenly jumped by 80%, to more than 1,500 cases, and experts are now alarmed. “It may have peaked,” says Hugh Pennington, professor of bacteriology at Aberdeen University and the government’s chief adviser on the subject. “But it may get 10 times worse.”

No parent thinks of killer epidemics when their child has a stomach upset. On that afternoon, last September, Rachael, 32, thought that Matthew just needed a rest and would soon be up and about. She was not, in any case, the type to bother doctors or elbow her way to the front of hospital queues. Until she stopped work to look after the boys she had been a quality checker in a local factory which made toilet seats, cooker handles and switches. Her response was the same as that of young mothers’ everywhere: she gave Matthew Calpol, a junior paracetamol, and waited for his tummy ache to pass.

Her son, too, was not a complainer. Despite being less than four years old, he had somehow assumed a prematurely adult role in their two-storey end-of-terrace house, opposite the post office on Lancaster Road. He had even been in on the birth of his brother, Tom, who was 19 months his junior. At night the boys shared an attic room and they played together every day. But he barely slept on that Monday night and on Tuesday he was again on the sofa. His mother was watchful and his brother was confused. But Matthew was hero-brave.

By Wednesday, it seemed to Rachael that he had more than a stomach upset. Matthew’s diarrhoea now contained traces of blood, which was being shed from his gut as the poison from the bug caused the lining to ulcerate and swell. She called the night doctor, who came at 3am. He was a young, dark-haired Lancashire man. He examined the child and ruled out appendicitis. Without tests he could not tell her more.

“If it gets any worse, you should phone me,” he advised her. Then he left on his out-of-hours round.

When she looked back later, Rachael felt that he had failed her. But most doctors would have acted no differently. Despite the growing number of high-profile food-poisoning reports – especially the Lanarkshire outbreak, which affected 400 people – and sporadic cases of sickness, brain damage and even death, few general practitioners have ever seen a case or learnt to spot the danger signs. There are plenty of other causes of diarrhoea, moreover, such as salmonella and campylobacter, which (at 6500 and 56,000 reported cases last year) swamp infections by the new E-coli.

North Lancashire’s doctors were especially backward in their readiness to deal with the problem. Because the organism is still only gaining a foothold, it has a remarkably patchy distribution of infection – many some places, few in others. Scotland, for instance, has more cases than England, with the east more affected than the west. Canada is worse hit than the United States, with its west suffering more than its east. There had recently been a small outbreak 20 miles south of Morecambe in Garstang, traced to unpasteurised cheese, and another during 1991, linked to a McDonald’s restaurant in Preston, but there was no sense of any local alert.

By Thursday, however, Rachael had seen enough and Stuart drove them over to the Royal Lancaster Infirmary, where they went to the emergency department. The blood in Matthew’s diarrhoea was worse than before and now he was now vomiting up anything he ate or drank. He looked pale and tired from lack of sleep and nutrition, but still he made little fuss. He was taken to the paediatric ward, ward 34, on the ground floor of the main hospital building. A consultant examined him and nurse took a stool sample to be tested in the hospital laboratory.

Rachael was told that the test would take days. At 5pm that Thursday, it was judged that nothing more could be done at the hospital, and Matthew was discharged. Rachael was told the problem was gastro-enteritis, and given a patient information leaflet. “This is a common infection in childhood which causes diarrhoea,” it explained. “There is often some vomiting as well. Most children will recover by 4-5 days, but sometimes it takes two weeks until everything is back to normal.”

She was reassured, as any mother would be. But on Saturday morning – day 6 of Matthew’s illness – she took him to see her GP. The boy now had a yellow tinge in his eyes, said that his back hurt and that his “wee won’t come down”. Also by now he was beginning to complain that he was feeling very sick. “Why can’t the doctor make me better,” he kept saying, when again they were told that there was no treatment for his condition, and he had returned to the sofa at home.

The following day, Sunday, Rachael phoned the hospital for the findings of the laboratory test. “We’ve had the result back this morning,” a nurse told her. “It is E-coli O157.”

Rachael was shocked. She had heard of E-coli. She had seen it on television. “That was what they had in Scotland,” she said, now alarmed. “What should I do?”

But although young children with E-coli are at the greatest risk of complications from the infection, the nurse had been given no guidance on any action and couldn’t offer any advice. “It doesn’t mean a lot to me,” is how Rachael recalls the nurse’s response.

*****

Matthew’s stool test was carried out in the Lancaster infirmary’s microbiology lab, on the third floor of the pathology building, a few steps from ward 34. Last year, it processed 70,000 patient specimens, with the same equipment and procedures that are used throughout most of the United Kingdom. Under the direction of Dr David Telford, a bearded 49-year-old consultant, there is a chief technician, two seniors, eight technicians and two assistants, who work around a rack of pale green benches, “plating up” and testing for bugs.

All specimens are routinely checked for salmonella and campylobacter, but most are not screened for E-coli. Despite the explosion in the number of infections, there are still thought to be too few to justify the time and money. But where the sample is bloody, a three-day procedure is employed to additionally search for this bug. The material is incubated overnight in a yellow “broth”, then scratched onto pink-jelly-coated dishes and left again until next day. If colonies of suspect bacteria have grown, some are studied on a slide with chemicals. Then more are incubated on a plastic strip, and the following morning the results are computed.

Matthew’s sample was received on day 4 of his illness and found positive on day 7. But again there would be questions about the delay this caused in reaching a diagnosis of his condition. State-of-the-art methods used at a few centres around Britain could have slashed his wait by two thirds. “If we got a specimen at four or five o’clock this afternoon,” explains Dr Peter Chapman of the public health laboratory in Sheffield, which uses these techniques, “we would be able to give you a 99.9% certainty result that it was E-coli O157 by 9.30am tomorrow.”

Why Matthew never got such service was, like the decisions to treat him as a non-emergency case, purely a question of priorities. Chapman uses more advanced and expensive tests, has specially-trained technicians and, since investigating an outbreak at a Sheffield old people’s home in 1983, has done world-class research on the organism. In contrast, the Royal Lancaster Infirmary does not have the time, and Telford’s main interest is campylobacter. Far from his staff being seasoned in O157, moreover, until last September they isolated the bug on fewer than one occasion a year.

That, however, was until last September, which saw more reports of E-coli infections in Britain than in any other month on record. Another of the organism’s unsolved mysteries is that there is a distinct annual season for human infections, which begins in May and peaks in the autumn – and which follows a kind of “blossoming” of the bacteria in cattle, which can be monitored several months ahead. As at hospital labs throughout the UK, the Royal Lancaster Infirmary’s microbiologists’ experience with the bug rapidly and frighteningly grew.

The most startling aspect was that Matthew’s case was by no means one-off, even in his neighbourhood. Four days before his illness began, a Morecambe girl, aged 14 months, went down with diarrhoea and vomiting caused by O157. Forty-eight hours after her, a local 11-year-old boy got the same. On the day before Matthew’s symptoms started, it was a 6-year-old girl, also in the seaside town. And then on day 8 of Matthew’s illness (the morning after his test results), Rachael was horrified to discover that Tom, his brother, also had bloody diarrhoea. In the following weeks there would be three more children, making eight, within three miles of Torrisholme.

The cases had many of the hallmarks of the outbreak in Scotland, but it was not until the fifth was confirmed that local doctors were warned to be vigilant. “We have a small cluster of E-coli O157 infection in Morecambe,” Telford faxed to 65 GPs on day 10 of Matthew’s illness. “We are notifying practitioners in the area so they can be aware of this when they see children with diarrhoea and so that they can have a lower threshold for taking stool cultures and for considering hospital referral.”

Rachael knew nothing of these other cases. Nor did the alert help Matthew. Despite the severe risk of complications, which can be expected in up to one fifth of cases involving children and old people, doctors decided not to admit any of those affected to hospital. Although antibiotics have no effect on the new E-coli, blood tests and close monitoring can help guard against possible problems like kidney failure. Yet these cost money or require scarce beds, so the advice was to stay at home.

Rachael was now coping with two sick children and, in the midst of this turmoil, an environmental health officer knocked on her front door. His name was Martin Brownjohn, a tall man, aged 42, who wore a dark suit and carried a black briefcase, from which he produced a thick questionnaire. He inspected her kitchen, looked in her fridge and asked her a string of questions. Where do you shop? What kind of foods have you bought? Have you been to restaurants or the chip shop lately? What kind of milk do you get? Have you been in the country, on farmland perhaps? Has your child been near any animals?

It was detective work, which he added to what he learnt from the other cases in what was now being called the “Morecambe cluster”. Although the natural home of the new E-coli is cattle, it has been found in lamb, poultry, fruit juice, cider, lettuces, mayonnaise, milk, eggs and many other foodstuffs, which may be cross-contaminated in processing plants, shops, restaurants and kitchens. Some infections are directly from animals, especially at open farms. It has been found in water supplies and paddling pools. And up to one in six reports are thought to be like Matthew’s brother’s case: spread from person to person. By comparing the responses from each of the children’s families, Brownjohn hoped to spot a common source.

The organism’s incubation period is between one and eight days, so Rachael told him about the visits to McDonald’s and the ice cream parlour, which also sold hot food. She expected that he would check these premises, but again the priorities question kicked in, and neither received a visit. Although ground beef is so often implicated that O157 has been dubbed the “burger bug”, there was felt to be no advantage in spending time and public money on inspecting the restaurants. It was nearly two weeks now since Matthew had been to either. It was felt that the moment had passed.

Just as importantly, none of the other families had mentioned them as possible culprits. The 14-month-old girl, it was noted from the questionnaires, had eaten Asda ham and had recently been on holiday abroad. The boy aged 11, plus Matthew and Tom had eaten Asda ham and drunk Thornburrow milk. The six-year-old girl had drunk Thornburrow milk and eaten sausage from a take-away. A two-year-old boy had possibly drunk the same milk. And another, aged 13, worked on a farm at weekends. One child had nothing that seemed to stand out as a strong candidate for the cause.

The ham, mentioned in four of the eight cases, and the milk named in four or, possibly, five, seemed perhaps to point to something, but they were treated by investigators with caution. These were mass-market products which you would expect to be cited by any group of families questioned. “It is dangerous to jump to conclusions,” says Steve Mann, manager of Lancaster’s environmental health department, whose offices overlook Morecambe Bay. “We thought about the possibility of a low-level contamination of a nationally-distributed product, but the investigation was basically getting nowhere.”

Rachael nagged Brownjohn, who called to see her again, but soon her insistence that the cause must be found was superseded by her other concerns. On day 10 of Matthew’s illness (when Telford faxed the warning to family doctors), the toxins attacking Matthew’s insides were making him so sick, with pain, diarrhoea and vomiting, that she called her GP, who came straight away and at last had the child admitted as an emergency to the Royal Lancaster Infirmary.

“I can’t cope any more,” she told him. “I’ve run out of bedclothes and everything.”

“I agree,” the doctor said, writing his referral letter. “I think it has gone on too long.”

When they arrived at the hospital, Rachael got the feeling that opinions about the situation had changed there also. This time Matthew was rushed into an isolation room and a nurse arrived almost immediately and, for the first time, took a blood sample. It went straight to haematology and the results came back while Rachael waited by his bed. The analysis showed that he was suffering from anaemia, with red cells bursting and fragmenting. It showed that his platelets – clotting cells – were low, and that his creatinine and urea – waste products – were much higher than they ought to be. The diagnosis was haemolytic uraemic syndrome, a complication of E-coli poisoning. It is the biggest single cause of kidney failure in childhood. Matthew was gravely ill.

He needed dialysis. He needed it right away. But such is the priority for paediatric renal units that Lancaster does not have one. There are 13 children’s kidney centres in the UK. A junior doctor hit the phones. Manchester was full. So a place was booked at Alder Hey, in the north-eastern suburbs of Liverpool. Stuart was called. Rachael’s sister came for Tom. And Matthew was wheeled out and into the back of a waiting ambulance for the 50-mile journey south.

*****

By this time, the investigation of the Morecambe cluster had enlisted the big guns of science. As Telford’s technicians confirmed each case as an O157 infection, a sample was posted to the government’s Central Public Health Laboratory in Colindale, north London, and an e-mail was fired weekly to the Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre, which is based at the same site. The central laboratory, which was founded in 1946, has an annual budget of £10m and employs some 400 staff. It is the nerve centre for tackling infectious diseases, such as Aids, tuberculosis and meningitis.

The lab’s scientists have published cutting-edge research on E-colis of every description. The core of these bacteria are minute tube-like cells, which have been classified through proteins in their skin (so-called “O” antigens) into 173 different sorts. Radiating from these cells are little tails, or flagella, which in turn are classified by another antigen (“H”), of which 55 have so far been found. Going a stage further, the O157:H7 organism, involved in the recent British outbreaks, has been sorted into around 80 different types, and the most modern technologies can go even deeper and fingerprint its DNA into thousands of individual strains.

Compared with other infectious agents, O157:H7 is not that common, but it is causing anxiety among scientists because it is incomparably nastier than most. It is astonishingly resilient: able to live in the kind of conditions that would kill other bugs. On farmland, it can survive in the soil for up to six months, while in kitchens it can cling to cool, dry surfaces and shrug off many household cleaners. Unlike infections such as salmonella and campylobacter, which require millions of bacteria to cause human sickness, as few as a dozen of the new E-coli are needed. And when it strikes old people, or children of Matthew’s age, it can leave them in a critical state.

Rachael’s sons’ samples, along with the other children’s, were sent to Colindale for what is called “phage typing”, which can give clues for investigating outbreaks. Using a handle-cranked contraption on a second-floor laboratory bench, technicians stamp dishes of E-coli with 16 viruses which attack bacteria. By later reading which viruses attacked what, the organism in the dish is given a rough-and-ready type. In the Lanarkshire outbreak, for example, where cross-contaminated ham had been sold by the local butcher, Scotland’s equivalent lab, at Aberdeen, identified each patient’s specimen as containing a type 2 E-coli bug.

But Colindale’s typing of the Morecambe cluster produced a startling result. Matthew’s and Tom’s specimens, along with the 11-year-old boy’s, came up as type 2. The six-year old girl’s, however, was typed 8. The girl aged 14 months who had been abroad was apparently infected by type 34. And there was a 21 and a 32 as well. Since an outbreak should involve bugs of the same type, it seemed that, whatever the source of Rachael’s sons’ infection, it was not the same as all of the others, despite the links of place, time and age. It looked as if the cluster was only a bizarre coincidence.

The environmental health officers took this as good news: there was no Lanarkshire-style outbreak on their patch. Brownjohn and Mann felt that nothing further would be gained by carrying out any more inquiries. No food or other samples were taken from Rachael’s home. The nearby allotment, where the children picked apples, was not investigated for infected manure. And, although both she and her boys regularly mixed with other children and parents, no contact-tracing was done to check the possibility of person-to-person spread. Even in the face of Matthew’s deteriorating condition, the investigation was brought to an close.

But, far from being grounds for confidence, the hidden story of the Morecambe cluster may have been more disturbing than even the Scottish crisis. It is hardly credible that an infection judged to be so rare that doctors, laboratory staff and environmental health officers give it scant attention should strike eight children in one place and at the same time without any explanation. It is possible that either the phage typing was wrong – and insiders say it often is – or, if they were infected with different types, then that suggests there is more E-coli around than has so far been acknowledged. In short, that Morecambe was the tip of some iceberg of hidden, unreported, infections.

The clue that there may have been more to know is found in statistics compiled at Colindale by the Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre. During the week that Matthew became ill, these showed a dramatic and unexplained leap in O157 reports. In the week before the first day of his illness there were 24 notifications in England and Wales – more or less last year’s weekly average. In the week beginning the Monday after, Day 8, during which he was admitted to hospital as an emergency, there were more: 52 reports. But during the seven days between – the week ending September 19 1997 – the numbers pouring in from labs such as Telford’s totalled a staggering 103.

What this spike in the graph points to may have been a national outbreak which was not so connected by geographic location to come to local authorities’ attention. With foodstuffs often transported hundreds of miles from central processors and packagers, Rachael’s boys may have been connected to many others by exactly the kind of “low-level contamination” which the Morecambe investigators had suspected. “We felt we were seeing a local aspect to a national problem,” says a member of the local team. “Intuitively, we felt that was the best bet.”

A review of the evidence stacked up so far supports this intuition. Most infections in healthy adults produce no or only minor symptoms. Most hospital labs do not routinely test for E-coli, so its true incidence is unknown. No statistics are compiled on e coli-related disease. And the number of deaths cannot be calculated because certificates rarely cite the infection. With the bug’s resilience and ability to trigger illness in extreme low doses, it could easily have got into a mass-market product last year, been distributed throughout the UK during September and caused apparently unconnected sickness in children from Land’s End to John O’Groats.

If Matthew was the victim of such events, the central laboratory could expose the fact. But again the child was let down by a system that undervalues the E-coli threat. Although Colindale’s phage typing sounds impressive and is carried out on all samples received at public health laboratory’s labs, it is a cheap, quick, crude and virtually clapped-out technology, devised half a century ago to classify salmonella. More than one third of all O157 strains are lumped together in this system as type 2 – far too big a group to track through the food chain. And although the more sophisticated DNA fingerprinting technique is available at Colindale, it is not routinely used, on grounds of cost.

Once more it was question of the priority for E-coli – and whether the specialists and authorities that are charged with fighting it are doing everything that the public would expect. “Everybody has limited funds,” says Tom Cheasty, a senior researcher at the central laboratory. “The way we are financed and staffed, we couldn’t do all the work that would be needed to be done on everything. We wouldn’t have enough hours in the day. If people spent more time looking at this bug they would have to spend less time looking at some of the others.”

But the new fingerprinting technique (called “pulsed-field gel electrophoresis”) could have analysed the DNA in Matthew’s and Tom’s samples and not only matched the precise strain of the organism present against the other Morecambe children’s, but also against those involved in all of the other infections reported to north London that week. Each family affected could have been interviewed as Rachael was and common sources readily identified, wherever in Britain they might be.

To fingerprint all of that week’s 103 samples might take a technician three months and cost £6000, but such DNA testing combined with new methods of detecting the organism in foodstuffs and bar-code tracing of products through the food chain, could transform the response to E-coli. Not only could rogue producers or packagers be nailed, but also bad practices at abattoirs, dangerous activities such as spraying animal remains and cattle faeces on farmland, and the continued sale of high-risk milk, could all be swiftly tackled. Some scientists believe there would be the long-term chance of eliminating the bug altogether.

Although Colindale cites the pressure of other work, the main beneficiaries of not using the new technologies may not be other research priorities, but the giant food and farming enterprises whose lapses may remain undetected. If tests linked disparate cases of illness such as the Morecambe victims’ with batches of common products, such as, say, ham or milk, public opinion could force severe government action, as it did over BSE. And after the wholesale slaughter of cattle brought about by inquiries into two dozen human deaths from new variant CJD, business could be forced into another round of costly remedies to clean up its act.

But if the winner is business, the loser is the consumer – leaving parents such as Rachael to think that illness must be due to something in the home. On the day that Brownjohn called and interviewed her, the things that stuck in her mind most strongly were questions about her habits. Which shelf in the refrigerator do you put cooked meats on? Do you always clean knives after cutting? Could you show me, please, how you wash your hands? Let me look at the kitchen again.

Brownjohn left her thinking that she was to blame for the state of her little boy’s health.

*****

On the evening that Matthew was transferred to Alder Hey, Rachael nevertheless felt elated, almost light-headed, now that he was getting the best. A Royal Lancaster Infirmary nurse went with them in the back of the ambulance, but Rachael ignored her and quietly talked with the driver throughout the journey south. Matthew was sedated and only woke for a moment when a tailback on the M6 to the east of Preston forced them onto the hard shoulder and he heard the rumble of wheels on cats-eyes. For a couple of miles they slid past columns of frustrated travellers, stealing perhaps a second of each’s thoughts before vanishing into the dark.

A few seconds more were devoted to Stuart, who drove behind the ambulance in a blue Vauxhall Belmont, his face sometimes glowing taillight red. He was 32, the same age as Rachael, stocky and fit, with dark hair and a moustache. He was often mistaken for the boxer, Barry McGuigan. He must have looked to some who observed that evening’s procession as if he was sneaking behind the emergency vehicle as a means of dodging the jam.

Dialysis worked wonders, despite the delay. Matthew perked up straight away. In an isolation room on Ward A3, there was plenty of cheerfulness. He looked a mess, with a tube from the kidney machine puncturing his left side, pumping 45 minutes in and 10 minutes out, to drain off the toxins from his system. At the same time he also had a tube into his hand because his blood was being transfused. But he started to take an interest in his strange new surroundings, allocating doctors and nurses to a pantomime, in which he played Peter Pan. Rachael had bought him a Peter Pan suit and he now longed to put it on.

“Tell me about happy things,” he urged his mother and father as they took turns to sit by his bed.

“We’ll take you home soon,” Rachael reassured him.

“Promise?”

“Promise.”

There was also good news to be had in Morecambe: the other children were getting better. Tom’s bloody diarrhoea passed after about a week, as the hospital had predicted would happen for Matthew. Even a little girl, the 6-year-old, who had also been diagnosed with the haemolytic uraemic syndrome, eventually got back to normal. There was always a risk of later kidney problems, but for the moment they all seemed well.

Their recovery put perspective on the E-coli issue: not every victim suffers badly. “Only about 5% to 10% of children who have bloody diarrhoea will get haemolytic uraemic syndrome,” explains Dr David Hughes, Alder Hey’s consultant paediatric kidney specialist, one of only 35 in Britain. “Of those who do, about half may need dialysis. And of those, between 3% and 5% may die. If you are a doctor in the community looking at this from one end of the telescope, it is very few patients who will reach the end that I look through.”

But Matthew’s dialysis had started too late and on day 19 of his illness, Friday October 3, he suddenly took a turn for the worse. As he was being weighed (about 2.5 stone) that morning, his right arm and leg suddenly shot out and he twitched alarmingly. His head rolled and one eye drooped. He was having some kind of fit. It was one of the syndrome’s neurological complications as the poisons shed by the O157 bug turned their attack against the child’s brain.

It did not necessarily mean permanent damage, but was a particularly worrying event. Hughes took Rachael and Stuart to one side and discussed the possible outcomes. He was a tall Glaswegian in his early 50s, who looked like a thin Donald Dewar, the Scottish Secretary. He towered over Rachael in his white coat, with his arms folded, and gave an up-front explanation. “Neurological symptoms are a bad sign,” he told her. “He may recover totally. But there may be some degree of long-lasting damage to his brain. Or – and you must be prepared for this possibility – he may die.”

Matthew went under a scanner the following day and then his parents retreated to Alder Hey’s ground floor restaurant and tried to come to terms with the crisis. Around them the life of the hospital seethed: babies in arms, sucking on bottles; toddlers trotting ahead of their fathers; anxious 12-year-olds shuffling sheepishly, not wanting to be thought of as children. It was a rare moment of connection for the separated couple. But they could do nothing but wait and pray.

On Sunday, 21 days since his symptoms began, their son went into a coma and was moved to the intensive care unit. The dialysis and transfusion tubes were now joined by one into his groin, to administer drugs, and two more into his nose. One of these passed into his stomach to feed him, while the other linked the unconscious three-year-old’s lungs with a life-support machine. His tongue was swollen and a gum shield was inserted to stop him from biting it. Rachael took out his Peter Pan suit and put it by the end of his bed.

One week later, Matthew opened an eye for 20 minutes, but this did not mean anything good. When Rachael lay beside him and stroked his hair he seemed to sob at the sense of her presence. But there was no other form of response from him: it was as if some part of her child had gone. “Wiggle your toes if you can hear me,” she whispered. And she would talk to him about his favourite place: Happymount Park, 20 minutes from their home. There was a big spiral slide there and bright coloured playhouses. The trees were full of birds.

Hughes had the job of explaining the options. This was not what had brought him into medicine. Ever since his days as a student he had wanted to be a paediatrician, and his sub-speciality, called nephrology, had always been stimulating enough. There is nothing as rewarding as sick children who get better. And even when they left him with a lifelong illness, their life’s quality could be dramatically improved. But in Matthew’s case, there was neither possibility. His brain was too far gone.

Rachael and Stuart took two days to decide to switch off his life support.

It was Stuart’s shift at the bedside when Matthew died, at 11.45pm on the 40th day of his illness. Stuart went and told Rachael before the nurses or doctors, and she hurried to take care of things. There were the marks of sticking plasters across her boy’s face. She cleaned them off and then washed him all over. Then she put him into his Peter Pan suit, and the next morning she finished the task. Matthew was wrapped in a grey hospital blanket and, with Alder Hey’s chaplain and a nurse on either side of her, she carried him down a long sloping corridor and out of the building, close to the Ronald McDonald House, and round the back to the mortuary. She was surprised by how heavily he rested in her arms. He had grown while he was ill.

In time, what had happened would sink in with Rachael and she would start to have hours and then whole nights when she stopped blaming herself for what happened. In time, Tom could see an older blond boy without running up and bursting into tears. In time, Stuart might talk about his son, but he has not done that so far. And throughout the health service, in time, the debate would begin about the need to upgrade the priority given to the threat from the E-coli bug.

“We had never seen a case like this before,” Telford explains, speaking for everyone involved in the system that let Matthew down. “Medicine isn’t planned. It’s reactive. It is about building on your experience.”

But before these times there was another motorway procession, as a black private ambulance, with Stuart driving behind, returned Matthew to the house in Torrisholm. Rachael carried him up to his attic room, where a friend had surrounded the bed with teddy bears, and she put him down, as if to sleep. There was nothing that she could do about what killed her child. All she could do was take him home.

MORE TOPICS:

Bactrim-Septra: a secret epidemic

Research cheat Andrew Wakefield