Reprint:

![]()

Victims of drug that took a hidden toll

The Sunday Times, August 21 2005

A special investigation by Brian Deer

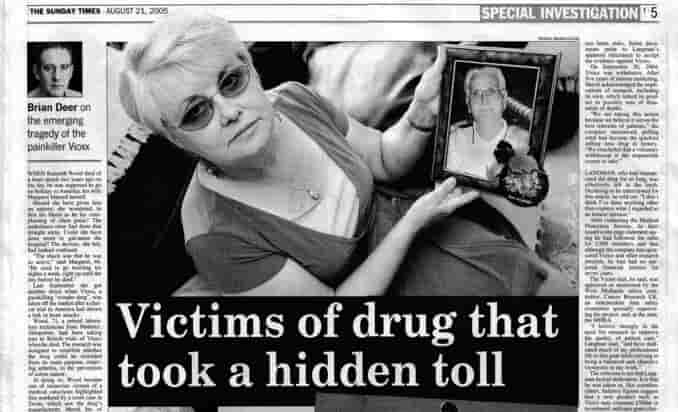

WHEN Kenneth Wood died of a heart attack two years ago, on the day he was supposed to go on holiday to America, his wife Margaret blamed herself.

Should she have given him an aspirin, she wondered, to thin his blood as he lay complaining of chest pains? The ambulance crew had done that straight away. Could she have done more to galvanise the hospital? The doctors, she felt, had looked confused.

“The shock was that he was so active,” said Margaret, 64. “He used to go bowling six nights a week, right up until the day before he died.”

Last September she got another shock when Vioxx, a painkilling “wonder drug”, was taken off the market after a clinical trial in America had shown a link to heart attacks.

Wood, 71, a retired laboratory technician from Madeley, Shropshire, had been taking part in British trials of Vioxx when he died. The research was designed to establish whether the drug could be extended from its main purpose, relieving arthritis, to the prevention of colon cancer.

In doing so, Wood became one of numerous victims of a medical cataclysm highlighted this weekend by a court case in Texas, which saw the drug’s manufacturer, Merck Inc of New Jersey, ordered to pay £141.1m in damages to the widow of another Vioxx patient.

Dozens of British lawyers are now soliciting clients, while some experts calculate the global toll linked to Vioxx at up to 60,000 deaths. “This,” Dr David Graham, a senior US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) official, told a stunned Senate committee last November, “would be the rough equivalent of 500 to 900 aircraft dropping from the sky.” He described it as “what may be the single greatest drug safety catastrophe”.

Although Margaret Wood has no plans to sue anyone, some lawyers believe she could have grounds. A Sunday Times investigation into the British connection to the Vioxx project has established that her husband was never told of all the possible risks when he was recruited for the trial.

This is the essence of what emerged from the court near Houston — that Merck did not disclose to patients all it knew about problems with the drug.

Margaret did not know, for example, that a doctor working on the trial had reported to Merck that the drug trial was “probably” to blame for Wood’s heart attack. “I’m very, very angry,” said Margaret when I showed her confidential documents last month. “I wasn’t aware that there were any risks at all.”

Her husband died in November 2003, 18 months after volunteering for the research. The trial, called project “Victor”, was financed by Merck.

Nor did Margaret know that evidence of Vioxx’s potential dangers had first been noted four years earlier. Even after this, the drug was backed by much of the medical establishment in America and Britain.

Just six months before Wood’s death, Britain’s leading authority on painkillers had dismissed rising fears over heart attack deaths connected to Vioxx as “speculation”.

The Wood case is part of a far bigger scandal now threatening to engulf Merck. When Vioxx was withdrawn, 20m people around the world, including 400,000 in Britain, were using the drug. Doctors have formally reported the deaths of 103 people in Britain, but the real figure may be as high as 2,000 according to some experts.

Why was such a potentially dangerous drug allowed to be prescribed so widely in Britain? Why was it backed so enthusiastically by experts such as Professor Michael Langman, one of the leaders of the Victor trial and an expert on painkillers? The answers are both complex and distressing. They begin with a paradox that Langman had been struggling with for more than 20 years.

LANGMAN, a former dean of Birmingham University’s medical school, became a figure of great influence in 1987 as one of the 36 members of the government’s drugs watchdog, the Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM).

Painkillers have long been Langman’s specialist interest, particularly aspirin and similar drugs such as naproxen and ibuprofen, known collectively as “non-steroidal anti-inflammatories” or NSAIDs. Although they are effective, particularly in osteoarthritis, they can also cause fatal stomach ulcers and perforations.

When Merck announced in 1999 that it had developed a similar drug without these side effects, Langman was understandably impressed. The new drug was based on Nobel prizewinning research by Sir John Vane, a British pharmacologist who had found that aspirin blocked two chemical messengers. One triggered the heat and pain of inflammation, while the other protected the stomach from ulcers. By blocking one but not the other, it ought to be possible to give relief without the usual risks.

Few new medicines are truly “miracle drugs” but this was how Merck sold Vioxx. To advance this image it recruited an army of consultants, Langman being among the most distinguished.

In April 1999 he sat with the Merck delegation when FDA advisers assembled at the Gaithersburg Holiday Inn in Maryland to consider the company’s application for a marketing licence.

“In my country there are hundreds of deaths a year — in all there are thousands — from NSAIDs complications,” he told the meeting. “It is the critical issue and if we have information that bears upon it I have a feeling, as somebody with an interest in public health, it’s our duty to make it known.”

Nine days later the CSM approved the drug for marketing in Britain. A leaflet aimed at British doctors stated: “In eight pooled studies of up to one year, Vioxx (average dose 25mg) reduced the risk of developing upper GI (gastro-intestinal) perforations, ulcers and bleeds by more than half compared to NSAIDs.”

Although FDA staff registered “serious concerns” about the analysis, Langman became the new drug’s champion. In one journal he declared that Vioxx-type drugs “are almost certainly associated with lower risks of ulcer and its complications, and probably no risk at all”. In another he later denounced rising fears over heart attacks as “a flurry of unjustifiable speculation and controversy”.

In 2001, at the peak of the Vioxx hype, Merck reportedly spent $160m advertising the drug. In Britain, where direct advertising is banned, the promotion was almost wholly through doctors.

“The world of relief is about to change,” screamed promotions issued for Vioxx’s British launch (including a coupon offering doctors a free clock). “True once-daily dosing for osteoarthritis patients . . . Selective, strong, simple.”

Merck also sought ways of broadening the market for the drug by demonstrating that, like aspirin, Vioxx was effective for more than just arthritis. Doctors prescribed it to reduce the inflammation caused by sports injuries, and in particular it seemed to have potential for inhibiting tumours, for example in colon cancer.

So while an American Merck trial code-named “Vigor” compared Vioxx — known generically as rofecoxib — with the painkiller naproxen for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, another trial — “Approve” — tested whether colon cancer could be stayed.

In November 1999 the safety committee monitoring Vigor met to discuss increased blood pressure, “excess deaths and cardiovascular experiences”

In October 2000 Merck supplied the FDA with a string of death reports involving heart attacks and strokes. In response, Dr Shari Targum, the FDA analyst, wrote in a report dated January 2001: “It would be difficult to imagine inclusion of Vigor results in the rofecoxib labelling without mentioning cardiovascular safety results in the study description, as well as the Warnings section.”

This advice was dispatched to other regulators around the world. Yet none of this was notified to patients such as Wood when a colon cancer trial in Britain was set up by Langman in partnership with David Kerr, who headed the Cancer Research Campaign Institute. The trial was established under the auspices of the main British ethics, research and regulatory bodies.

Kerr, now a professor at Oxford, was a rising star in the new Labour medical firmament — close to Alan Milburn, who was health secretary, and his expertise repeatedly acknowledged by Tony Blair.

The Victor trial was approved by a West Midlands medical ethics committee in November 2000 and aimed to recruit 7,000 volunteers at 168 British hospitals, plus more in Australia and New Zealand. Half would get Vioxx and the rest a placebo. They had all received “potentially curative” surgery for colon cancer.

Victor was trumpeted throughout the medical profession. “The idea of maintaining all the beneficial possibilities of aspirin but without the side effects was clearly very attractive,” said Desmond Laurence, emeritus professor of pharmacology at University College London, who was invited to join Victor but refused.

Wood was among the first volunteers for Victor. The “informed consent sheet” that the Royal Shrewsbury hospital gave him in May 2002 itemised only these possible side effects: “tummy pain, dizziness, fluid retention leading to ankle swelling, increase in blood pressure, indigestion and heartburn, mild headache, itching”. There was nothing about heart attacks or anything too serious.

Informed consent documents obtained by The Sunday Times show that even by the time the project was abandoned in November 2004 the full range of hazards was not revealed.

Wood’s death certificate read: “1 (a) Myocardial rupture, (b) Acute myocardial infarction, (c) Coronary artery atheroma (furring of the arteries).” Decoded, Wood died of a heart attack so massive that it would have resembled a gunshot wound.

What the certificate did not say was whether Vioxx was involved, so it came as a shock to Margaret when I read her a confidential report from Merck giving the opinion of a Shrewsbury hospital doctor.

“The investigator felt that the myocardial infarction was not related to disease/other illness,” said the report. “The investigator felt that the myocardial infarction and myocardial rupture were probably related to study therapy, and that the coronary atheroma was possibly related to study therapy.” In other words, the doctor, reporting privately to other doctors, said that in his view it was probably the Vioxx that had killed Wood.

THE $250m verdict in Texas, after a five-week hearing, followed claims that Merck had lied about the drug’s risks, an allegation that it strongly denied. The company has said that it will appeal. The dispute could cost Merck $20 billion, according to Wall Street analysts, one third of its total value.

The core question is why the firm took so long to act. In papers disclosed for the litigation, company e-mail chatter discussing fears of cardiovascular risks dates back to 1997. In that year researchers from London’s Royal Brompton hospital warned that Vioxx-type drugs could trigger heart attacks.

According to Merck there was no reliable evidence until its Approve project, testing Vioxx’s use against colon cancer, spat out preliminary numbers last September. “New and unexpected data emerged showing an increased risk,” a spokesman for its British subsidiary said. “Within one week of learning those results, Merck acted in what it believed was the best interest of patients and voluntarily withdrew Vioxx from the market.”

However, confidential documents obtained in the investigation raise questions over whether what the company has said publicly reflected what it knew about possible hazards. In Britain the first heart attack deaths were flagged up at the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) within nine months of the product’s launch.

No less disturbing were reports of fatal gut damage, the problem Vioxx was intended to solve. “There have been a number of spontaneous reports of GI perforations, ulcerations and bleeds associated with rofecoxib,” MHRA staff reported confidentially to the CSM in July 2000. “While in some instances these may be related to concomitant medication, or use in patients with known high risk of GI complications, the event rate is considered significant.”

The CSM considered the matter in December 2001. The minutes show that Langman was asked to stay in the room “to answer questions” even though at the meeting to license Vioxx he had withdrawn due to a possible conflict of interest, given his links with Merck and its financial support for his research. He was deemed to be needed in the room as the authority on painkillers.

After Langman left the room, the regulators limply concluded that “sufficient concern (about heart attacks) now exists from different data sources that it would be prudent to advise prescribers and patients by updating product information”. Yet five months later Wood joined the Victor trial without receiving any warning of serious heart risks. Some documents point to Langman’s apparent reluctance to accept the evidence against Vioxx.

On September 30, 2004, Vioxx was withdrawn. After five years of intense marketing, Merck acknowledged the implications of research, including its own, which linked its product to possibly tens of thousands of deaths.

“We are taking this action because we believe it serves the best interests of patients,” the company announced, pulling what had become the quickest selling new drug in history. “We concluded that a voluntary withdrawal is the responsible course to take.”

LANGMAN, who had championed the drug for so long, was effectively left in the lurch. Declining to be interviewed for this article, he told me: “I don’t think I’ve done anything other than express what I regarded as an honest opinion.”

After contacting the Medical Protection Society, he later issued a one-page statement saying he had followed the rules for CSM members and that although the company had sponsored Victor and other research projects, he had had no personal financial interest for seven years.

The Victor trial, he said, was approved or monitored by the West Midlands ethics committee, Cancer Research UK, an independent data safety committee specially supervising the project, and, at the start, the MHRA. “I believe strongly in the need for research to improve the quality of patient care,” Langman said, “and have dedicated much of my professional life to this goal while striving to bring a balanced and objective viewpoint to my work.”

The criticism is not that Langman lacked dedication. It is that he was taken in, like countless others. Industry figures suggest that a new product such as Vioxx may consume £500m in investment; and once giant clinical trials such as Victor are under way, the corporate imperatives to see the drug profitably marketed can shoulder aside appropriate caution.

“I’m sure he believed the data,” said Professor Kim Rainsford, editor of the journal Inflammopharmacology. “I hold Mike (Langman) in very, very high regard and so I was a little concerned to see him come out so strongly in support of this drug. But whether he’s done the right or wrong thing here, I think you’re right. There was so much hype that everyone had to jump on the bandwagon.”

Others believe there are wider implications for the supervision of medical research. Dr Evan Harris, Liberal Democrat MP for Oxford West and Abingdon and the party’s science spokesman, said it was “unacceptable for patients in a trial to have withheld from them information about the risks of serious side effects”.

He added: “Clinical trials are critical to the development of medicine and science, and that is why the apparent failure of the research ethics system to act on emerging concerns about the risks in this case suggests that reform is needed.”

Nobody has yet got in touch with Margaret Wood to explain what role Vioxx may have played in her husband’s death. Nor has anyone told her about the compensation scheme in place for the Victor trial. “They’ve never told us anything,” she said. “The only contact I’ve had is when I rang the hospital to ask what to do with his tablets. They said, ‘Take them to a chemist’. And that was that.”

Vioxx death toll may hit 2,000 in UK

The Sunday Times, August 21 2005

Brian Deer

THE families of as many as 2,000 British patients who died after using the painkiller Vioxx could join a potential multi-billion-dollar lawsuit against the drug’s manufacturers.

Lawyers for many of the relatives are considering filing claims in US courts against Merck, the pharmaceuticals giant, after the Legal Services Commission decided not to fund any cases in Britain.

The worldwide damages bill for Merck of £12 billion, predicted by Wall Street analysts, could rise even further after a landmark verdict in Texas on Friday when a court found the company negligent in the death of Robert Ernst, 59, and awarded his widow £141m.

A Sunday Times investigation today reveals that volunteers taking part in a clinical trial of the drug in Britain were not shown essential safety information, including warnings of potentially fatal hazards.

A total of 103 suspected Vioxx-related deaths have been officially notified in Britain. Most died of heart or gut complications after taking the drug. But calculations by The Sunday Times, based on known levels of under-reporting by doctors of medicine-related deaths, suggest that the true toll is closer to 2,000. About 60,000 people worldwide are estimated to have died from the drug.

The families of the dead will be joined by patients who survived but who blame serious conditions, such as strokes and paralysis, on the drug.

The Sunday Times evidence is similar to some of the revelations to emerge in the American courts, where 4,200 Vioxx cases are pending. Information about risks, available to the company and its experts, was not promptly given to patients.

In one British case, Kenneth Wood, 71, a retired Shropshire laboratory technician, died of a massive heart attack while taking part in a trial to see if the painkiller could also be effective in treating colon cancer.

A confidential Merck report, not revealed to Wood’s widow, described his death as “probably” caused by the drug. Other participants who suffered problems included a 73-year-old Leeds man who died from the complications of stomach bleeding; a 78-year-old man from Grimsby who developed angina; and a Yeovil woman, aged 64, whose heart failed after she started taking Vioxx.

Informed consent documents and other confidential papers show that Wood was not told of any serious risks and that mounting concerns among scientists and regulators, which had surfaced several years earlier, were kept from trial participants.

The trial, codenamed Victor, started in 2002 financed by Merck and was led by two of Britain’s most senior doctors. Professor Michael Langman, former dean of Birmingham University medical school, has been a member of the government’s committee on safety of medicines since 1987. Professor David Kerr of Oxford University is a leading figure among Labour health advisers and devised plans to reorganise Scotland’s health service.

Both men issued statements defending their actions. “The Victor study was run to the highest ethical and scientific standards,” said Kerr.

Merck achieved a worldwide market of some 20m users, including 400,000 in Britain, by promoting Vioxx as a miracle drug. It was said to offer all the painkilling and other properties of aspirin, but without the commonest side effect: stomach ulcers. Doctors prescribed it for pain control for everything from arthritis to sports injuries.

The documents that have emerged suggest evidence of serious problems with Vioxx which were downplayed. Enthusiastic marketing of the drug continued until its sudden withdrawal last year.

The company has said that it will fight every case and will appeal against the Texas verdict. “We believe that the plaintiff did not meet the standard set by Texas law to prove Vioxx caused Mr Ernst’s death,” said a member of Merck’s defence team.

Earlier this year the company’s British subsidiary insisted that it had acted promptly on information about risks: “We are confident in our research and how Merck has communicated about Vioxx.”

The history

Vioxx is an anti-inflammatory painkiller made by Merck, based in New Jersey, America. It was launched in Britain in 1999 Merck believed Vioxx would revolutionise pain relief, offering the benefits of aspirin without the older drug’s risk of stomach ulcers

Elderly people suffering from arthritis were the main patients, but doctors also prescribed it for other kinds of pain, such as that caused by sports injuries

Concerns were raised after research linked the drug to heart attacks and bleeding in the gut At the time of its withdrawal in 2004, 20m people around the world, including 400,000 in Britain, used Vioxx

More than 4,200 claims have been lodged against Merck with courts in America – including one by Carol Ernst, left, who was awarded more than $250m this weekend

MORE TOPICS:

Bactrim-Septra: a secret epidemic

Research cheat Andrew Wakefield