Reprint

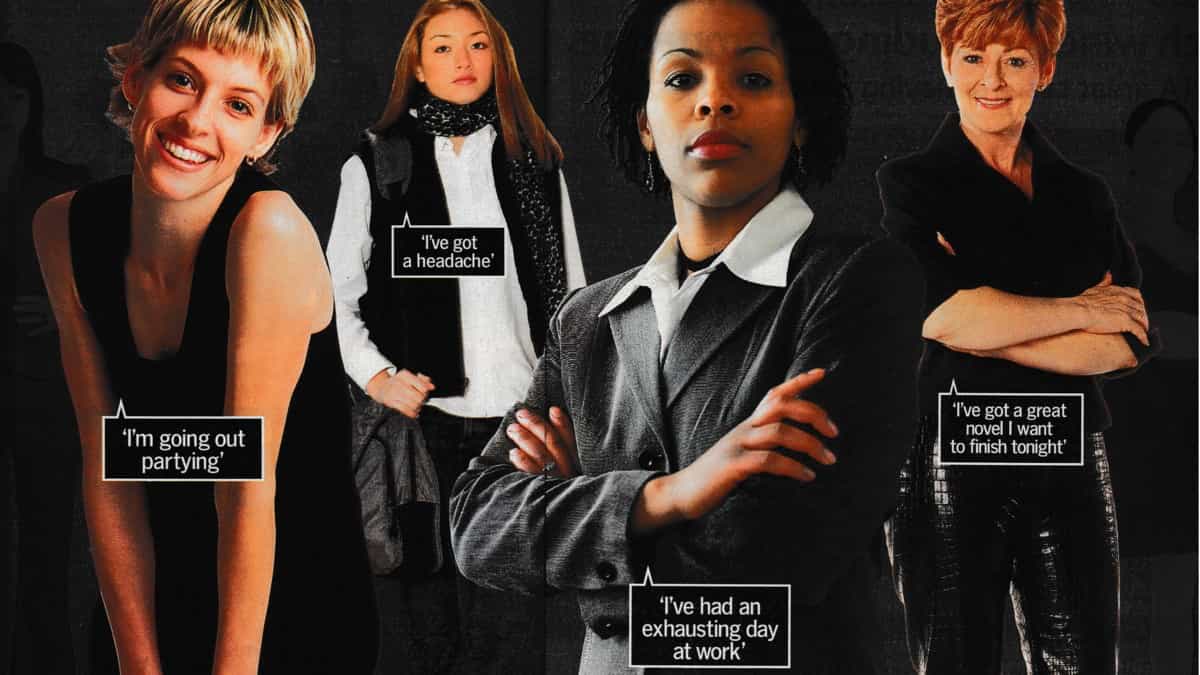

![]()

Love sickness

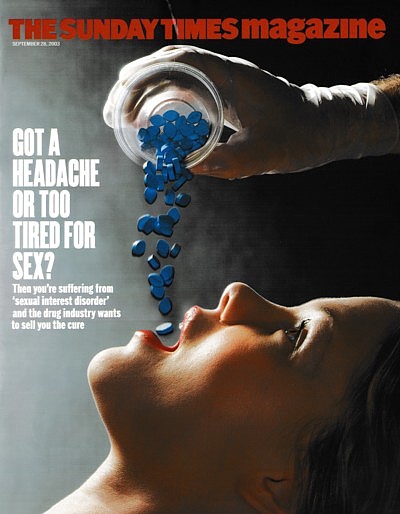

If you don’t want to drop everything and have sex right now, you’re among the 1 in 3 women suffering from Sexual Interest Disorder. That’s what some doctors think. Is it part of a crusade by pharmaceutical giants to bring more sex into the bedroom? By Brian Deer

The Sunday Times Magazine

September 28 2003

Nine years before she would announce the discovery of a new disease, Dr Rosemary Basson, consultant in the Centre for Sexual Medicine at Vancouver General Hospital, Canada, got a phone call from a medical research company working for the New York-based drug giant Pfizer. Would her clinic be interested in joining a trial of Viagra, the now-famous penis-stiffening blue pill?

Today, sitting at a grey steel desk in her 9-by-12ft white-painted office, she smiles, recalling the ignorance of the caller: he didn’t know “generalised” from “situational” dysfunction. But she accepted his offer, which brought a tidy wad of dough that would strengthen her department’s work. The British-born Basson was at the time nudging towards her fifties, and struggling to advance understanding of vaginismus, an anxiety complaint in which a woman seems to tighten in reflex opposition to penetration.

She was no great researcher. Her love was clinical medicine: hands-on caring for patients. Taking referrals from throughout the province of British Columbia, she saw only the most intractable sexual problems that had defeated family doctors or smaller hospitals. Of her caseload, 60% were women, mostly complaining of the pain condition dyspareunia, with men presenting with erection problems or difficulties with ejaculation.

She was no great researcher. Her love was clinical medicine: hands-on caring for patients. Taking referrals from throughout the province of British Columbia, she saw only the most intractable sexual problems that had defeated family doctors or smaller hospitals. Of her caseload, 60% were women, mostly complaining of the pain condition dyspareunia, with men presenting with erection problems or difficulties with ejaculation.

With a demeanour that reminds me of an English sitcom actress, Basson had published nothing in medical journals before the Viagra call came through. And although she holds a professorship in the University of British Columbia’s psychiatry and gynaecology departments, records show that in the year before Viagra’s launch in 1998, three projects she hoped to undertake went unfunded due to lack of wider interest.

But the landscape changed in the blue pill era as profits from the penis poured in. Although by no means Pfizer’s most popular line (grossing only a quarter of Lipitor, the world’s No 1 prescription drug), Viagra brought the company windfall revenues: currently $2 billion a year. And with the launch of “me too” competitors – such as Cialis from Eli Lilly, and Levitra from Bayer and GlaxoSmithKline – the Cinderella speciality of sexual medicine was suddenly dressed for the ball.

These days, Basson snags sponsorship deals like a sports star spotted by Nike. Pfizer commissioned her to look at the effects of Viagra in women with sexual arousal difficulties. Then came finance from Lilly to psychologically profile patients. More Pfizer work followed on women’s orgasm problems, then “questionnaire validation” for Procter & Gamble. Currently, she is testing a new oestrogen receptor blocker for her longtime companions at Pfizer.

Nourished by funding, she blossomed with ideas that have now lifted her to guru status. Mostly promoting what she calls a “new model” of female sexuality, her journal publications jumped from a single paper indexed by the Medline database for 1999, to three for 2000, six for 2001 and seven for 2002. She wins finance to lead panels and to attend international conferences concerned with “female sexual dysfunction”. And she’s currently co-authoring a global textbook that will be translated into half a dozen languages.

Having scaled this platform, what she says from it is startling, “It’s as big as [the feminist sexologist] Shere Hite,” she claims. Arguing that healthy women in established relationships may experience “interest” but rarely “desire” before sex with their partners, she goes on to claim that many of those who don’t may be suffering from a mental illness. Out goes passion as motivation for lovemaking, and in comes a diagnosis for a medical condition that she compares to a broken leg or appendicitis.

With industry-funded colleagues, she has suggested, astonishingly, that one third of all women may suffer from this condition – this “sexual interest disorder”, as she calls it. “If they truly have no interest in sex, yes, you could say they have a disorder,” she tells me on the phone, setting me scrabbling for a flight to Vancouver. “It’s a disorder because it’s out of line with the expected situation, and the range that seems to be normal.”

Can this be right? Now is the time to find out. Rosemary Basson is the new Queen of Desire. Even as we spoke, her ideas were being prepared for a sexual dysfunction brochure to be pounded out for doctors around the world. Footnotes to her textbook will cascade through the literature, giving the impression of a new-found consensus. And in a softly-softly move, official disease definitions are being targeted for wholesale revision.

But is she using industry help to understand women? Or do those who pay the piper call the tunes? Is a well of unfulfilment at last being recognised, or is modern life being fashioned into a disease? At a time when “big pharma” is hunting sex-related products that could dwarf Viagra’s sales, is Dr Basson’s recent rise a sign of social maturity, or of foundations being laid for new drugs?

“Why has she been anointed? That’s a good question,” Dr Leonore Tiefer, a New York clinical psychologist and author of A New View of Women’s Sexual Problems, told me before I flew to the beautiful Canadian west coast city squeezed between mountains, sea and the US border. “I’ve been to all the relevant sexological meetings since before you were born, and she wasn’t at any of them.”

*****

Well, she has been at some – at least in recent years. I saw her in Paris in July. Basson had flown in at industry expense as vice-chair of the Second International Consultation on Erectile and Sexual Dysfunctions – which, although almost entirely financed by at least seven drug companies, brought a thousand doctors and scientists from all over the world to the vast Palais des Congrés, west of the Arc de Triomphe.

Claiming to be “transforming data into knowledge and knowledge into action”, the £1m conference’s aims, like a similar meeting four years ago, were to hammer out definitions of sexual dysfunctions; to agree means of measuring them in both men and women; and to create benchmarks for trials of new products. The visual landscape was dominated by motor-show-sized stands for Pfizer, Lilly, Bayer and GlaxoSmithKline.

Into this event she strode, in a sleeveless cocktail dress, to unveil her new model and disorder. Presenting the findings of a powerful international committee she chairs, which has met over the past two years to rule on definitions of female problems, she stood at a lectern and rattled through blue slides as if reporting from some frontier of knowledge.

Her model, in a nutshell, rejects conventional wisdom about what makes women want sex. Whether from the austere teachings of 1960s sexologists, such as William Masters and Virginia Johnson, or from headline-grabbing feminists such as Shere Hite in the 1970s, Basson fears we’ve got the message that women’s responses are like men’s – or, if they’re not, then they ought to catch up.

Au contraire, she argues. Women are different. But not in the way feminists suggest. While men may be prisoners to testosterone-driven urges, trying to mate with what moves and pull the ring on what doesn’t, Basson thinks women mull precoital calculations enough to double their cellphone bills.

“When a woman senses a potential opportunity to be sexual with her partner,” she explained in a recent article in the Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, “although she may not ‘need’ to experience arousal and resolution for her own sexual wellbeing, she is motivated to deliberately do whatever is necessary to facilitate a sexual interaction as she expects potential benefits that, though not strictly sexual, are very important.”

To me, this sounds sneaky, but she shows us a slide: a reinforcing feedback loop of sexual interest. Starting with “One or more reasons for sexual activity; not currently aware of sexual desire”, Basson takes her audience clockwise around a diagram that she says maps the sexual encounter. “Willingness to be receptive,” the cycle continues, then “subjective arousal”, “more intense arousal and responsive desire”, “emotional and physical satisfaction”. And, at cigarette time, “positive influence on motivation”.

In less than bonkbuster language, she elaborates on this process with an erection-killing description if ever there was one. “The increased emotional closeness, bonding, commitment, tolerance of each other’s imperfections, and expectation of increased wellbeing of the partner all serve as highly valid motivational factors that activate the cycle.”

There’s a sidebar to all this about “information processing”, but “need a hard shag” is nowhere on the screen and even “orgasm” has dropped off the map. As she elaborated in the International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology last year: “In this cycle, departing from the traditional one… [physical] arousal is experienced before desire, and orgasm is not mandatory for a normal response.”

As a gay man, I luxuriate in the ninth row of the conference hall feeling eerily untroubled by all this. But Basson is proposing a concept that, should her campaign succeed, could transform medical involvement in sex. “I have presented a model that more accurately depicts the responsive component of women’s desire and the underlying motivational forces,” she wrote in 2000. “The purpose is to prevent diagnosing dysfunction when the response is different from the traditional human sex-response cycle, and to define subgroups of dysfunction. The latter is necessary before progress in newer treatment modalities, including pharmacological, can be made.”

*****

As her slides sped by, many of her mostly male audience talked among themselves, fired off text messages or fiddled with drug company gifts. After an afternoon session on phosphodiesterase (PDE-5) inhibitors, which sent a hundred fingers tickling free Viagra computer mice, Basson’s lecture on the finer points of female motivation failed to trigger a mexican wave in the Palais des Congrés. There was still no pill for an ugly spouse that, if prescribed, wouldn’t send you to jail.

But her model was a centrepiece for the Paris event’s sponsors: there’s gold in that feedback loop. With men’s treatable concerns mostly confined to (a) penis hardness, or (b) penis hardness, drug companies are sure how to keep consumers happy. The benchmark of success is conspicuous. But if women are more subtle and their concerns less clear, then industry needs to know PDQ.

Enter the disease she unveiled from the lectern: the previously unheard-of sexual interest disorder. “There are absent or diminished feelings of sexual interest or desire, absent sexual thoughts or fantasies and a lack of responsive desire,” was how her committee’s report described the problem. “Motivations (here defined as reasons/incentives) for attempting to become sexually aroused are scarce or absent.”

More dry words, but do they mean or change anything? You can bet your underwear they do. Describing disorders is like sizing goal mouths: allowing the guys with the tape measures and spirit levels a say in what reaches the net. “Diseases are not just out there in nature,” says Dr Richard Smith, editor of the British Medical Journal (BMJ), who questions the very existence of many industry-backed dysfunctions. “They are creations in many ways, and where you draw the boundaries, and what you define as a disease, is a very tricky business indeed.”

The boundaries Basson challenges are some of medicine’s most authoritative, thrashed out over decades of debate. Currently, the consensus-setting Manual of Mental Disorders, issued by the American Psychiatric Association – which in turn feeds into the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) International Classification of Diseases – recognises a condition called “hypoactive sexual desire disorder”, described as “a deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity”.

This might sound similar to what she’s suggesting, but, as so often, the devil is in the detail. The concept of “interest” is plainly bigger than “desire”, so already we get dysfunction inflation. But even widening the net with a broader definition is only the start of the reconstruction she seeks. At present, the psychiatric association has an essential requirement to diagnose a disorder: “marked distress or interpersonal difficulty”. And the WHO includes a crucial prerequisite that for a person to have a problem they must be “unable to participate in a sexual relationship as he or she would wish”.

But these criteria will be dumped if the plans unveiled in Paris gain a foothold in official classifications. In place of the requirement that a patient must complain of a problem, Basson wants to substitute “descriptors”, including a “scale of distress” which, according to her committee, includes “none”.

“So,” I debate her on the phone from London before catching my flight to Canada. “You are saying that women can have this sexual interest disorder even if they don’t feel they have a problem themselves?”

“Yes,” she says. “It’s a bit like saying a man can’t ejaculate. Now, he’s not trying to be a father. He doesn’t care. He enjoys everything he does – the arousal and intercourse – if he wants to. He just doesn’t ejaculate, and he doesn’t mind. Does he have a disorder or not?”

Ouch. “I’d say he probably did.”

“Why?” she hits back. “If it doesn’t bother him?”

“For the same reason you could have a broken leg and not be concerned,” I joke.

“I agree with you on both of them,” she says. “You’ve still got a disorder. I think the man’s got a disorder. And it’s reasonable to say the woman’s got a disorder, even though it doesn’t bug her. Because it’s a kind of assumption that most women have an interest in sex.”

Hey presto, the numbers with a disorder hit the ceiling like a guy with no problem at all. Although research published in June from the world-famous Kinsey Institute in Indiana suggests that only 7.2% of women complain of this problem, according to a stream of papers recently pumped into the medical literature, the number of women who say they “lack interest in sex” is between one third and 40%.

Here’s a vision of a market to restore vigorous appetite to the most dysfunctional pharmaceutical boss.

*****

On either side of the waiting room at Vancouver’s Centre for Sexual Medicine are tables loaded with industry literature – for the most part aimed at men. Questionnaires are in vogue, and I find myself scanning them, while Rosemary Basson finishes up with a patient. “Do you remember a time when you felt better about your ability to have sex?” asks GlaxoSmithKline’s brochure, Intimacy, Depression and Antidepressants. “Do you find yourself falling asleep after dinner?” inquires Organon’s leaflet Testosterone and Andropause.

I tear a four-by-eleven-inch quiz form from a pad that gives no clue to its publisher or printer. But I have seen it before, and even know who wrote it: psychologist Dr Raymond Rosen of New Jersey. Asking stuff like “How do you rate your confidence that you could get and keep an erection?” and “During sexual intercourse, how difficult was it to maintain your erection?” it draws me into scoring myself on a scale of 1 to 25 – with “21 or less” a reason to see the doctor.

The form looked official, perhaps from the Vancouver hospital, but it was really a crafty Pfizer sales tool. Rosen, a professor at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Piscataway, is a pre-eminent drug company consultant in this field – financed by Pfizer, Merck, Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Procter & Gamble and Icos – and has cornered the market in consumer surveys that lay the bedrock of industry campaigns.

But confusions are as common in the field of pharmaceuticals as they are in the world of double glazing. A Basson abstract on the Medline database, for instance, implies that a study of Viagra comes from the Vancouver hospital – while the text shows it’s really from Pfizer. The grandly-named International Index of Erectile Function and the Female Sexual Function Index are merely formats for Rosen’s Q&As. And the influential Consensus Development Panel on Female Sexual Dysfunction is just 19 specialists, Basson included, of whom 18 admit receipt of industry money.

Even the Paris conference wasn’t quite what it seemed – at least to some of those who sat around me. Vice-chair Basson, two members of the scientific committee and various other participants all told me that the Palais des Congrés gathering was a WHO event. “It’s a consultation to them, to guide them when they make their decisions,” Basson explained. “Plus the financing of the consultation comes from them.”

This was news to the WHO, who e-mailed me from Geneva dissociating the agency from the meeting. Although participants told me they thought that travel grants for a “faculty” of around 200 key opinion-formers (a free hotel room each and $1,700 expenses) came from the United Nations health body, the whole shebang was essentially an industry jamboree, as was the previous Paris bash four years back.

“For the 1999 conference, WHO agreed to co-sponsorship on the understanding that there were no commercial interests involved,” the director-general’s office told me. “We later learnt that satellite symposia [advertising segments] organised by pharmaceutical firms were included in the programme. We asked the organisers to remove this from the programme, but due to the intervening lapse of time, our records are incomplete on the follow-up to this request.”

This didn’t stop a 750-page colour book being published from the 1999 conference bearing the WHO crest – and I found a certain murkiness, even for pharmaceuticals, when I tried to nail down the book’s status. Co-authored by Rosen, it purported to be published by “Health Publication Ltd”, a company with nothing more than a Jersey, UK, post office box. Another Jersey box in the name of “Signet Media”, to whom conference cheques were paid, didn’t come up on the 3.3-billion-page world wide web. And the registered address of the organisers’ domain was the unhelpful not @available.com.

When I raised these with Basson, she said she didn’t know, but she must have felt the hand of business. The Paris events were just two of seven industry-backed gatherings in the past six years that laid the ground for the definitions she announced. The founding event, held in May 1997 at a hotel on Cape Cod, was sponsored by nine drug companies. “The meeting is completely supported by pharmaceutical companies, and half the audience will be pharmaceutical representatives,” Rosen wrote to colleagues at the time. “Only investigators who have experience with, or an interest in working with the drug industry have been invited.”

Basson knows the score. It’s how the system works: how industry holds the ring for medical discourse. “There’s not a lot of money in medicine, period, and for research in the area of sex it’s just dismal,” she tells me, arguing that without such support leading experts around the world would never meet face-to-face. “So what do you do? You just sit in your little clinic and you can’t help anyone.”

But he who pays the piper at least expects to enjoy the music – and not to hear notes of discord. “Industry has a narrowing effect on how we see problems through various mechanisms, all of which are to do with money,” says Amy Allina, policy director of the Washington-based National Women’s Health Network, who points to the many causes of poor sex lives that may be overlooked in drug-based research.

What happens, for instance, to headaches, stress, fatigue or boredom? What about the lack of physical exercise or poor diet? And what about life with a partner you don’t like, much less want to be physically involved with? Does industry want to pay for highlighting such topics? You had better believe it does not.

“Bias is very subtle,” says Smith of the BMJ. “There are many more people who want to do research than receive funding, and if you have the huge resources of the pharmaceutical companies, you can say you’ll fund these people and not those people because these people view the world in a way that looks good to you.”

Industry’s current favourite is a dramatic expansion in the numbers alleged to be dysfunctional. According to scores of scientific papers, including one with Basson’s name on it, 43% of women (and 31% of men) have a sexual “dysfunction”, “problem” or “complaint”. And as New Jersey psychologist Dr Sandra Leiblum, who has worked with Rosen for years, told an event sponsored by 17 companies in 1999: “Especially remarkable was the finding that one out of three women said they were uninterested in sex.”

Remarkable, indeed, since they didn’t exactly say that – and there is no data that any complained. The figures being used to build the new market have been cribbed from work led by a Chicago sociologist, Dr Edward Laumann, (sponsored, like Rosen’s medical school, by the philanthropic arm of Johnson & Johnson). But all he asked women was: “During the past 12 months, has there ever been a period of several months or more when you lacked interest in having sex?”

Well, so what if there was? Does that fix them as uninterested? Is that a basis for diagnosing a disorder? If a woman isn’t turned on by the father of her children, does that really mean she’s mentally ill? “I think we should be very suspicious of these figures,” says Dr Ellen Laan, professor of clinical psychology at Amsterdam University.

Laumann’s figures might have faded like a magazine sex survey, with little more reaction than “fancy that”. But in 1999 his data resurfaced on the new tide of industry cash. For some reason, the otherwise prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association republished his seven-year-old research as an “original contribution”, now co-authored by industry man Rosen. Two months later, the journal issued a “correction”. “Since 1997,” it said, “Dr Edward O Laumann has served on the Scientific Advisory Committee to Pfizer.”

*****

While Basson makes tea, I study her office, which faces downtown Vancouver and the Burrard Inlet. Often when I have interviewed doctors and scientists, their walls have been spattered with certificates and awards – and occasionally a Nobel prize. But her space is spartan. Her priority has been patients. She’s a late bloomer in the pharmaceutical garden. Pride of place goes to a poster of a Eugene Smith photo and a group portrait of the King’s College London Medical Society when she was a student there in 1967.

So why front a campaign with a working clinician? Why not wheel out some established big cheese? As we talk in her office, that mystery fades: if she didn’t exist, they might need to invent her. Of course, they need a women to medicalise female sexuality – and the key players in urology are all men. They need a medical doctor – and the field of sexology is overrun by PhDs. To pluck a leader from Canada is a political masterstroke: it plays well in both the US and Europe.

But the married mother-of-two argues that medicalising sexuality is the opposite of what she intends. Her model, she says, is “bio-psycho-social”, requiring doctors to elicit a rounded picture. “All of us aren’t like little robots,” she tells me. “Because the pharmaceutical industry is now interested, and maybe now there are drugs for various aspects of the physiology that can go wrong, it doesn’t mean it’s all a medical entity.”

Some of her research, she says, points to Viagra’s limitations, and she argues that the impact of defining sexual interest disorder may actually reduce drug prescribing. “The data to date suggests that most women who go ahead and have sex with their long-term sexual partners do it for reasons of emotional closeness,” she says. “There’s not going to be a drug to increase emotional closeness.”

Well, I think she’s wrong. Ecstasy does that now, admittedly with quite some downside. Testosterone, meanwhile, is used to raise women’s libido, and oestrogen to create “wellbeing”. Drug companies are doing nicely with products for inattentiveness (Ritalin), shyness (Paxil or Seroxat) and life’s futility (Prozac). And last month American researchers reported that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram was effective in “compulsive shopping disorder”.

In my view, I told her, her ideas could be used to sell Viagra to women today. Although research looks thin on its role for female problems, mysterious new conditions, such as “vaginal engorgement insufficiency” and “clitoral erectile insufficiency”, are emerging, for which her model may be invoked to address. If, as she says, (a) different stages in the sexual response cycle reinforce each other, and (b) physical arousal precedes feelings of desire, she may be opening the door for prescribing drugs for arousal when the patient has ticked “lack of interest” in the quiz.

But more important is the direction of scientific research, for which her model may map new routes. For hospital ethics committees to approve new-product trials, they must first have a disease for the product to treat. No disease, no treatment. End of story. But if the campaign Basson launched to change definitions succeeds, “sexual interest disorder” becomes a bona-fide problem to which remedies may be properly addressed.

There will be no quick fix and, as research goes on, her announcement in Paris may be forgotten. But, no question, from the lectern she proposed a new paradigm that chimed well with the spirit of big pharma. Just as television audiences have fractured in the face of cable and satellite, so markets for medicines are threatening to shatter as gene-based personalised therapies loom larger. As generic manufacturers gnaw at patent rights, the research-based industry lusts for new blockbusters for us all to swallow daily for life.

As Rosen’s colleague and Paris attendee Leiblum hints at the priorities in the introduction to her book, Getting the Sex You Want: “While the search is on for a miracle potion or fail-proof device that will transform sex and make it magical, it is my belief that ultimately, women hold the tools necessary to get the sex they want. It is their willingness to do what needs to be done – whether it means taking hormones, starting therapy, or believing that they are entitled to sexual pleasure.” [My italics]

By an astounding coincidence, Leiblum was in Vancouver and hijacked my first session with Basson. But back to one-on-one, we return to my worry that the British doctor may be pathologising untroubled, healthy women, bringing medicine where it doesn’t belong. It seems to me that if a person isn’t interested in sex and doesn’t want to train a partner to change that, they might take up tennis, read Anna Karenina, or in some other way get on with their life. I also found it troubling to see a model implying that women merely responded to men.

“I could argue it from either side,” she says. “I could argue it from a feminist side, saying, ‘Look, if you don’t care about a disorder, even though you’re totally different from everyone else on the planet, who cares? It’s not a diagnosis. It’s not a disorder.’ Then you could argue it from the other side and say, ‘Look, if your appendix is inflamed and it’s pus-y, it’s going to burst,’ and you reply, ‘I don’t care. I don’t mind the pain. I do not have appendicitis.’ Well, of course you have appendicitis. Whether you care about it or not, in the medical world, is irrelevant.”

“But that doesn’t happen,” I say. “Except in weird religious groups. If you’re in a situation when you have no interest in sex – even an ‘abnormal’ lack of interest in sex – but it doesn’t bother you, and you’ve not presented yourself to physicians saying you have a problem, your position is that their condition still exists.”

“That’s right,” she says.

“Now that creates the opportunity for all your little questionnaires in the waiting room – tick, tick, tick, tick. ‘Speak to the doctor about this’, and the doctor will flog you a drug.”

“But women who have no interest in sex and don’t care are not going to take a drug,” she hits back. “Why would they? They don’t care.”

“Because then you’re into fashion, social pressures, cultural pressures.”

“If you’ve got no interest, you’ve got no interest. By definition.”

“But if you turn on your TV and it says, ‘Are you feeling this?’ and you start to think: ‘Maybe…’ Then it says: ‘Are you bored?’ And you think: ‘Oh, well…’ And maybe it ties in with depression. ‘Maybe the reason you’re depressed is because you’re not getting enough sex.’ And you say: ‘Oh, I’m not interested in sex…’ And they say: ‘Well, we have a product for that’.”

“We haven’t got a product for women’s sexual interest.”

Well, no. She is right. Not yet.

The blue pill era has barely dawned. We’ve only five years of erection enhancement. There will be many more conferences, foreign trips and research papers before big business sells drugs to turn us on.