Reprint

![]()

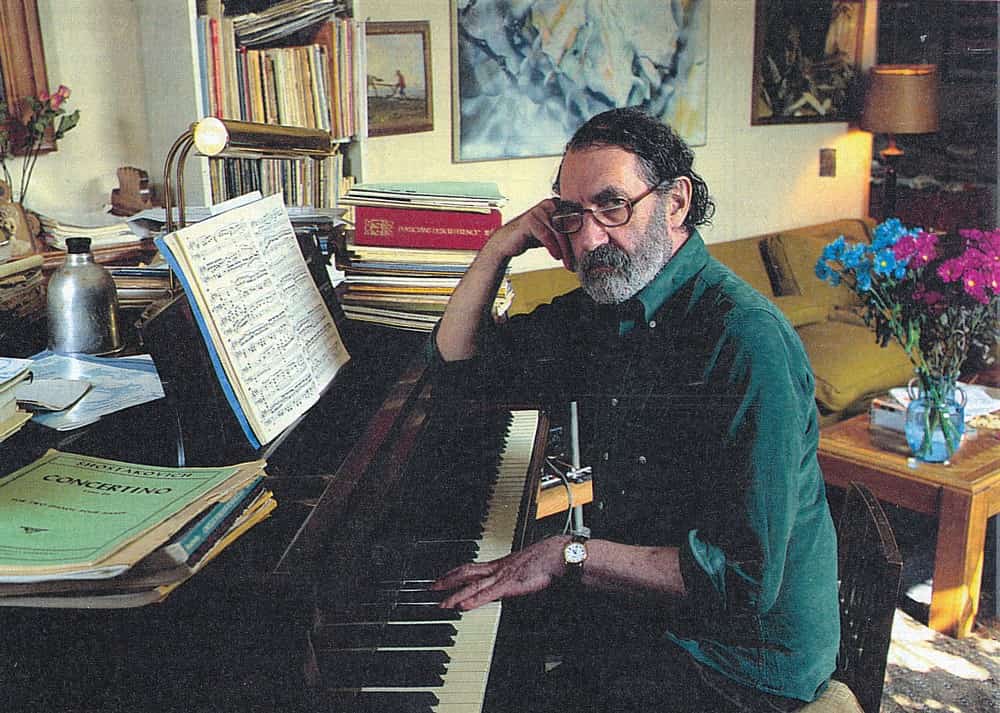

A life in the day of Joe Sonnabend

The Sunday Times Magazine, July 19 1992

Joe Sonnabend, Aids specialist, talks to Brian Deer, who also took the photograph

Dr Joe Sonnabend, 58, is one of the world’s leading Aids specialists. After growing up in Rhodesia he moved to Britain and was a pioneering researcher into Interferon at the Medical Research Council. He owns a house with his sister Yolanda in St John’s Wood, London, but since 1974 has lived and worked in New York. He has two sons

“If you ask me, as a scientist and doctor, what lies at the heart of the Aids epidemic, I can only say that the answer, for me, is a baby grand piano. It sits here in my apartment, smack in the middle of Greenwich Village, from where I’ve watched the health crisis unfold since the very first day. In the eye of the tornado my piano represents calm.

Mostly I play in the mornings before I set off for my laboratory at St Luke’s-Roosevelt medical center, or for the Community Research Initiative on Aids, where I’m medical director. My time before lunch is split between the two locations. But first I like to get in a few pages of music — something romantic usually, or a bit of Bach.

Actually I have four keyboards. I bought the grand on installments, starting in 1974 when I moved to America. Then there’re an upright, left to me by a patient who died. And a harmonium, left to me by a patient who died. And a little electronic organ, left to me by a patient who died. Two hundred and eighty of the people I’ve cared for have lost their lives so far.

People are always giving me things — instruments, pictures, cheques. The average physician in the United States makes $90,000 a year, but I’m lucky if I’ve got two hundred bucks in the bank. Most of my patients are young and never got medical insurance. I have a British awkwardness when it comes to billing sick people. I have to do it but, you know, it never quite works out as a business.

Before I leave home each morning the other thing I do is take my blood pressure. Nobody seems surprised that it’s so high, but I’ve been on medication for the last few months and I feel much better for it. I treat myself, but once a month I see a cardiologist, who checks I’m getting it right.

If it’s a lab morning I do experiments. My scientific background is in virology and years ago I upset a lot of people by doubting whether HIV was a sufficient explanation of Aids. As I see it, HIV might be everything, something or nothing. Amazingly, after 10 years of this epidemic, we still can’t be sure. My own research aims to nudge governments into funding open-minded inquiry, and the press says it’s beginning to happen.

If it’s a CRIA morning I take a taxi to the office at West 26th Street, where my assistant Bill throws the latest problems at me. We run community-based trials of promising new treatments and have had some limited success in keeping people alive. Half the time I’m on the telephone, discussing research protocols, sorting out labs to do tests and talking to other physicians.

That gets me into trouble as well. There’s a lot of rivalry between organisations and we have to tread carefully with the US government’s National Institutes of Health and with AmFAR, the American Foundation for Aids Research.

I’ve been a thorn in the side of the Washington top brass right from the start. My doubts about the relationship between HIV and Aids were bad enough, but they’ve never forgiven me for standing up at a meeting in 1985 and suggesting that the ‘Aids virus’ supposed to have been discovered in America by Robert Gallo had in fact come in the post from the Pasteur Institute in France. Nobody really knew what I was talking about at the time, but now they do.

AmFAR is kinder, because I helped set it up. Dr Mathilde Krim, its farsighted director, used to research with me on interferon and we’re good friends. Once I came back from a conference and found her in my apartment. She’d had it painted and furnished while I was away. She said it wasn’t right for me to be sleeping on the floor.

After a sandwich or a quick lunch in a diner I usually go over to my doctor’s office in a tenement building on West 17th. A few of my patients started coming to me before the epidemic, but now most come because of my reputation for not prescribing AZT — the so-called anti-Aids drug. As a scientist and doctor I can’t see how it can meaningfully work. I’m working on a paper to show how long my patients survive compared to those of other doctors.

The support of my patients is probably the best thing in my life, but I know that some of them are worried about me. I’m really unhappy here and want to go home to pursue my research in Britain. When one patient found out he came round with his sister and some friends one weekend and redecorated and furnished the office. I was so grateful because the place was just terrible before. But I felt sad and guilty as well.

Most sessions in the office stretch late into the evening and I’m lucky to be away by nine or 10. Then I do a house-call or go back to my apartment and deal with the half-dozen messages that will have accumulated on my answering machine. I get faxes as well, on a machine given me by a patient. I get through as much of this as possible before my dinner is delivered.

I usually read one of the medical magazines then — The Lancet, for instance. And every so often I see the publication I launched myself — and feel more bitter than usual. It started as Aids Research, but then got taken over by Bob Gallo and renamed Aids Research and Human Retroviruses. That was one fast shuffle of the cards.

Recently I’ve been reading stories about myself. Many misrepresent my views, but a nice one the other day called me ‘the man who invented safer sex’. This referred to my campaign for condoms before they were widely used for protecting health.

I call them patients, but they’re friends really. It’s hard or me to draw the line. Being Jewish I think I’ve got a strong sense of community, of looking after one’s own. And having spent most of my life as a researcher I never acquired the doctor’s ability to stay detached. There’s no way of switching off from death and misery.

Life is not all Aids, however. I go to the movies at least once a year — the last thing I saw was Alien 3 — and I’ve just finished reading Art Speigelman’s cartoon book about the Nazi camps, Maus. When I go to bed I might switch on the TV in the bedroom; my favourites are old horror films, but I usually fall asleep before the end.

If I’m wide awake with anger I might play the piano, which must be good for my blood pressure. My mother was a doctor. She died when I was 13, but got me into the instrument very young. My father went to Africa to study the Bantu. A painting of him in a South African army captain’s uniform looks down on me as I play.

I’m always learning something new. At the moment it’s a sonata by the composer Alban Berg. It’s technically complex. I’ve spent weeks trying to get it right. Sometimes I wondered whether it isn’t stupid of me to attempt things that are so very difficult.”

RELATED:

Brian Deer reports the UK’s first recognized AIDS death