Reprint:

![]()

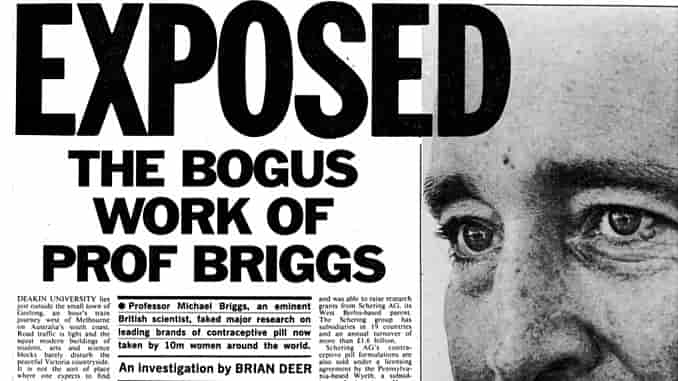

The pill: professor’s safety tests were faked

The Sunday Times, September 28 1986

By Brian Deer

Social Affairs Correspondent

RESEARCH into the long-term side effects of a new generation of contraceptive pills was fabricated by a British scientist. His deceptions put a question mark over safety checks on pills being taken by up to 2m women in Britain and 10m worldwide.

An investigation by The Sunday Times into the research of Professor Michael Briggs, one of the most influential international experts on contraceptives and an adviser to the World Health Organisation, has revealed scientific fraud on a large scale.

Briggs’s bogus research purported to assess possible risks of heart and arterial disease in women after prolonged use of the pill. His area of work was on changes in fats in the blood, or “lipids”, which are thought to be as serious a threat as cancer to women taking the pill.

His research culminated in the biggest survey of these risks yet published and was extensively relied on in drug company advertising to promote the pill’s safety claims. The companies which make the pills involved, Schering AG of West Germany and Wyeth of the United States, financed much of his work through grants.

A number of products, including Logynon and Trinordial in Britain and TriLevlen and Triphasil in the United States, were granted government licenses on the basis of submissions including work by Briggs over more than a decade.

After an investigation in Australia, Europe and the United States, Briggs was tracked down by The Sunday Times in Spain where he now lives with his wife, a British-registered family planning doctor. She is a joint author of some of his scientific papers.

In a four-hour interview at his new home in Marbella on the Costa Del Sol, Briggs, aged 51, admitted serious deceptions in his research, among them that he had:

* Pretended to have organised studies of the effects of oral contraceptives which he had not done. He said the studies had been organised by someone else, but declined to name this person.

* Produced a study on animals which he had never done. This study, on beagle bitches, later helped persuade the British government that arrangements which previously delayed the granting of licenses were no longer necessary.

* Included in scientific papers complex biochemical test results, the origins of which he couldn’t name. One paper, he said, he was unaware even of the country in which the analyses were purported to have been done.

“It is a sad story,” said professor Max Elstein, who sits on the drug safety committee of the health department’s Committee on the Safety of Medicines. “The whole scientific community was bamboozled over this.”

Schering and Wyeth paid for Briggs to present his work at special international symposia and then financed its publication in one-off books. Through publication in these books and in journals, Briggs’s bogus findings have become part of medical literature. They are now found in the work of nearly all major contraceptive researchers.

“This is a very serious matter,” said Dr James Rossiter, chairman of the ethics committee at Deakin University, Australia, where Briggs’s bogus work was written. “This material was published and circulated by drug companies to doctors who don’t have time to read the references.”

Schering and Wyeth have denied knowledge of the frauds and said last week that they had no responsibility to ensure that research they supported was fair. Wyeth, which has continued to advertise Briggs’s data, despite knowing that it was in question, said doctors would not allow such promotions to affect their prescribing.

But both drug companies said they would no longer be using the research. “We are not going to cover up for, or try to defend, Michael Briggs if he is wrong,” said Glen Branham, vice-president of Wyeth International in Pennsylvania. “I would like not to believe it, but I have to believe there is some fire with the smoke.”

Briggs produced most of his bogus research while holding the post of professor of human biology and head of the sciences school at Deakin. However, the studies he described were based on research equipment that was not available at the university, on drugs that were illegal in Australia, and on groups of women patients assembled at a speed and ease other researchers found impossible to emulate.

A year ago, an international meeting of contraceptive research specialists in Berlin held an emergency discussion about Briggs after growing incredulity at the speed with which he produced highly complex data on trials on women. His work has also been considered at the World Health Organisation.

Many experts privately believe all of Briggs’s research is now in doubt, but have focused on a series of papers he produced while at Deakin. An analysis of these papers reveals extraordinary flaws.

At a meeting in Chicago last week, senior staff of the two drug companies urged The Sunday Times to stress that the public was protected through research by other scientists – whose findings resembled those of Briggs.

The companies have known for a year that Briggs’s research was in dispute and the UK Committee on the Safety of Medicines said that it would be a breach of regulations if it were not told of doubts over data. The US Food and Drug Administration said it would launch an investigation into the continued use of Briggs’s work in promotions to doctors.

If the research had been done in the United States, the FDA said it would have been subject to stringent checks, but these powers did not extend abroad. “This could be a very important story,” said Dr Solomon Sobel, head of its hormone division in Washington. “You should pursue it.”

The Briggs story continues in Deer’s Sunday Times “Focus”

MORE TOPICS:

Bactrim-Septra: a secret epidemic

Research cheat Andrew Wakefield