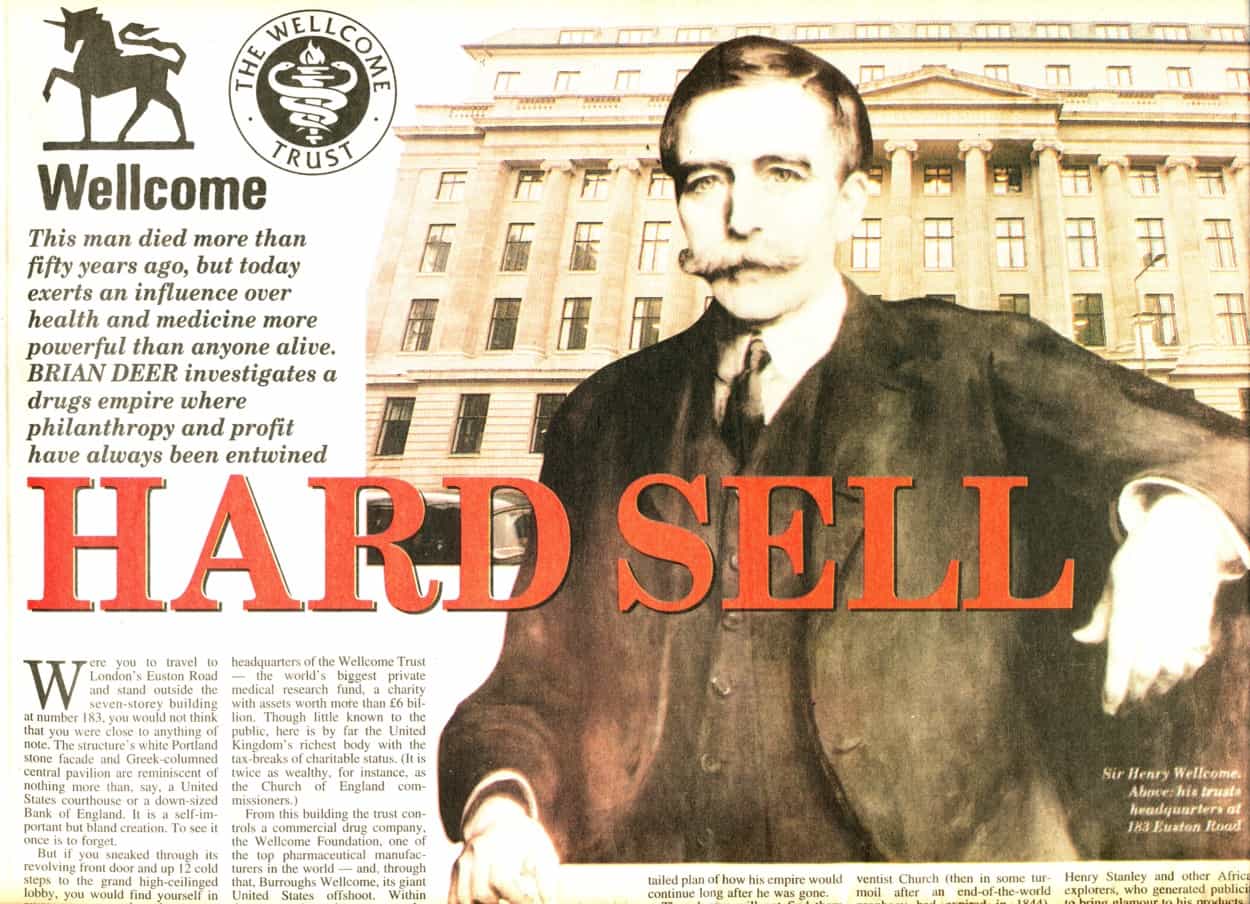

In his will documents of 1932, the American-born pharmaceuticals pioneer Henry Wellcome devised an ingenious plan that was to give him more power over health and medicine after his death than would be possessed by anyone living. But, following this two-part Sunday Times news investigation by Brian Deer, plus Deer’s revelations about the company’s flagship product, marketed as Bactrim, Septra or Septrin, Wellcome’s trustees broke up their founder’s empire, releasing billions for biomedical research.

Reprint

![]()

Hard Sell

The Sunday Times, 27 February 1994

By Brian Deer

Were you to travel to central London and stand outside the seven-story building at 183 Euston Road, you wouldn’t think, to look at it, that you were close to anything of note. The structure’s white Portland stone facade and Greek-columned central pavilion are reminiscent of nothing more memorable than, say, a US courthouse, or a downsized Bank of England. The external elevations are self-important but unimaginative. To set eyes on them once is to forget them.

But if you sneaked through the revolving front door and up 12 cold steps to the lobby, you would find yourself in elegant spaces that shout most loudly of money. Number 183 Euston Road is the creation of the late Sir Henry Solomon Wellcome, perhaps the premier architect of the modern pharmaceutical industry, and the builders didn’t skimp on the job.

On the day it opened in 1932 (only four years before Henry died), it was a point of distinction that no wood or cheap metals should be visible to the visitor’s eye. The floors and walls were of fine imported marbles, the doors and windows exclusively of bronze. It was all to the taste of a president, or king. A style to suit the man.

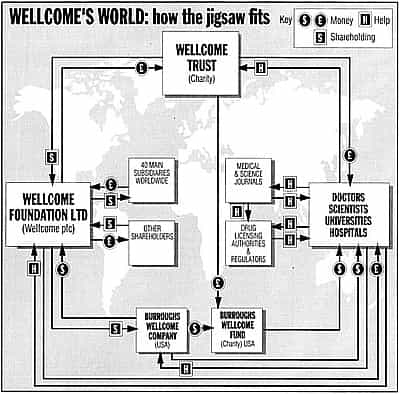

The interior’s grandeur does perfect justice to 183’s extraordinary role. This building is the headquarters of the Wellcome Trust, the world’s richest private medical research foundation, with assets of more than £10 billion. It is the wealthiest British charity, declaring assets twice as great as the Church of England commissioners. From here the trust controls Wellcome plc, a top multinational drug company. And, through that company, it controls Burroughs Wellcome, its United States offshoot, and the charitable Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

From these companies and charities, through grants and sponsorships, government agencies, universities, hospitals and scientists are influenced all over the world. The trust distributes more money to institutions than even the British government’s Medical Research Council.

In offices on the building’s first floor, decisions are reached that affect lives and health on scales comparable with minor wars. In the conference room, high above the street, and in the meeting hall, in the basement, rulings in biotechnology and genetics are handed down that will help shape the human race.

If all of this is news to you, then some Wellcome products may be more familiar. Wellcome plc, which trades, confusingly, as the Wellcome Foundation (and which not long ago decamped to a green-glass tower at 160 Euston Road), most notably sells AZT, the anti-Aids drug, which last year commanded a market of £248m. More commercially notable is its herpes treatment, acyclovir, sold as Zovirax, grossing £760m.

There are also over-the-counter cough and cold products, Sudafed and Actifed, which brought in £141m. And some 50 other treatments, from an antibacterial, marketed as Septrin, Septra or Septran, to a gout remedy, allopurinol: Zyloric or Zyloprim. Total sales revenues are more than £2billion annually. More than enough to keep the front door spinning.

*****

The special place of honour at 183, is a shrine to the founder, in the basement. By the stairs near the entrance is an oil painting of the man: middle-aged, with a handlebar moustache. In cabinets to the right are examples of the merchandise and promotions that got his empire going. There are personal items, such as his honours and medals, and his soft-spined, preacher-style, Bible.

On a winter evening among these things, you can almost feel his presence. But if Henry Wellcome lives on – and in some ways he does – it’s in the shape of a document that his trustees today choose not to place on display. Soon after he was knighted, by King George V, and shortly before the building was officially opened, he knew that he was approaching the end of his life, and he filed a remarkable will.

With a lengthy hand-written memorandum, he set out a framework for how his empire should operate, even half a century after his death. A copy is held by the Charity Commission in London, and with the rise in the wealth and influence of his organisation, they have become some of medicine’s most important documents.

What Henry Wellcome set out was a double-edged scheme to run a business and a charity together. The flagship would be a philanthropic body – now the Wellcome Trust – enjoying the image and tax benefits of magnanimous, public-spirited generosity. But, behind this would operate “industrial organisations”: straight up-and-down for-profit corporations. Today these trade under the names of the Wellcome Foundation Ltd (long wrongly assumed to be charitable), and its parent, Wellcome plc.

The scheme was essentially a Masonic contrivance. Henry Wellcome was a lifelong Freemason. And, despite the efforts of many among Britain’s great and good who have since administered his affairs on the board of trustees, so successful was this merging of profit with charity that it has given a dead man a tighter grip on medicine than that enjoyed by few who are alive.

Urging that there should be “frequent consultations” between the charitable and the commercial arms, Henry Wellcome revealed in the memorandum the scale of his ambitions for his empire’s future. “With the enormous possibility of development in chemistry, bacteriology, pharmacy and allied sciences,” he predicted, “if my desires and plans are carried out in the way of research co-operation with the several industrial organisations, there are likely to be vast fields opened for productive enterprise for centuries to come.”

*****

If any of the exhibits at 183 are pivotal, it must be his personal Bible. For many years the pages have been opened at a passage he marked in thick pencil for personal contemplation. “And thou shalt bestow that money for whatsoever thy soul lusteth after,” he selected from verse 26 of Deuteronomy 14. “For oxen, or for sheep, or for wine, or for strong drink, or for whatsoever thy soul desireth.”

Henry Wellcome was born in 1853, and grew up in Minnesota. Two uncles and his brother were Christian ministers, and his father was a noted lectern-thumper of the fundamentalist Second Adventist Church. This austere congregation was at the time in some confusion, after an end-of-the-world prophecy had – in 1844 – gone seriously unfulfilled.

He acquired from his father a tough-minded religiosity and, more usefully, a facility to persuade. Young “Hank”, as he was then known, worked for a time in an uncle’s drugstore, in the frontier settlement of Garden City. And it was there, aged 16, that he came up with a Big Idea that he was to deploy pretty much all his life.

Realising that it was not so much what a drugstore sold that mattered, but the way that it was presented, he bottled lemon juice and advertised it as invisible ink, with a pitch to shame a snake oil salesman:

Wellcome’s Magic Ink

THE GREATEST WONDER OF THE AGE

This is something entirely New and Novel!

DIRECTIONS

Write with a quill or golden pen on white paper.

No trace is visible until held to the fire when it becomes very black.

Prepared only by

H.S. WELLCOME

Garden City, Minn.

His drugstore experience propelled him to pharmacy college, where he further developed his idea. It was less the science of medicine, he realized, than it was the marketing that created the profits. Taking the next step, in 1880, he moved to Britain, at the age of 26, and went into partnership with one Silas Burroughs: an even better salesman than himself.

Medicines were still mainly powders or liquids, so the two men first started a European agency for the newfangled style of American tablets. Wellcome prepared attractive-looking chests, containing such age-old remedies as ipecacuanha, strychnine and quinine. And in 1884 he laid claim to their format under the registered brand name “Tabloid”.

Tabloid chests of medicines (some of which are displayed at 183) were often given away to influential people, and became the start of the modern industry’s famed “freebies”. Beginning as complimentary first-aid kits for the rich and powerful, the idea was soon expanded to provide foreign travel expenses and financial support for useful contacts.

Wellcome and Burroughs were especially noted for pioneering door-to-door selling to doctors. Pursuing the Big Idea, they realised that people became physicians often for reasons less to do with compassion than for family, prestige or wealth. Burroughs, in particular, was adept at calling on physicians with a gift and free samples, and departing with the knowledge that a new crop of patients had been won to the Tabloid brand.

Henry had comparable business acumen, but found time for a personal passion for exploration. Inheriting from his father a belief in the Bible’s literal truth, he spent vast sums from the Tabloid coffers to scour Africa for evidence of prehistoric white tribes. In one project in Sudan, he hired 4,000 people to dig for four years, trying to prove that evolution was wrong.

In such bizarre ventures, the Wellcome founder’s personality came dramatically to the fore. Donning the white pith helmet of the imperial explorer, he would distribute peacock feathers among his native workers who abstained from alcoholic drink. As an alternative to such carrots, there was also a stick: he would whip men caught asleep on watch.

These aspects of his character have caused a few headaches to those concerned with his empire’s image. Much of his personal archive is claimed to have been destroyed, while a biography commissioned in the 1940s from a staff member (who noted Henry’s “inflexible spirit of intolerance”) has been kept locked away by the Trust.

None of these headaches has been worse than dealing with his marriage (in 1901) and divorce. His wife, Syrie Barnardo, daughter of Britain’s most celebrated child-care philanthropist, Dr Thomas Barnardo, was 27 years his junior. And according to her friends, Syrie disliked Henry’s cruelty: most notably alleging that he used to beat her with a sjambok, a South African cattle whip.

Perhaps in reaction, Syrie used his foreign trips as opportunities to court other men. Gordon Selfridge, an American-born department store magnate, was one. Then, at some time around 1911, she met, had a relationship, a child, and then a marriage, with the young Willie Somerset Maugham. He was England’s most celebrated playwright of his time and, somewhat awkwardly for Syrie, was gay.

But according to the suppressed Wellcome biography (once briefly seen by someone writing about Syrie), the effect on Henry of his wife’s affair with the playwright “soured his character for the remainder of his life”. By the time he came to draft his will and memorandum – the biography concluded – the old man had lapsed “into a morbid misery only to be soothed by a vicious preoccupation in his own interests”.

*****

If Henry Wellcome’s ghost stalks 183’s marble and bronze, he might well be thinking that, with the passage of years, in some sense, the last laugh was his. At the time of their divorce, he could hardly stomach Syrie’s betrayal, and the humiliating rumours about Maugham’s sexuality. But in the final quarter of the twentieth century, it was precisely such lifestyles that was to create vital markets upon which his empire would thrive.

In the 1960s, which saw gonorrhoea cases jump 300%, the Wellcome Foundation was an obscure English enterprise, strong on publicity (and caffeine-based home remedies), but with few bright scientists – mostly in the US – and a modest reputation in cancer. But as “adultery” fell out of popular usage, and “promiscuity” began losing its stigma, the empire based in Euston Road was on the spot with relevant products.

The 1970s saw the rise of its antibacterial, Septrin, Septra or Septran, used commonly for urinary tract, and some sexually-transmitted, infections. The 1980s saw the unveiling of Zovirax, its antiviral for herpes simplex. And the 1990s was its decade for AZT, its therapy for HIV/Aids.

Septrin (in the UK) and Septra (in the US) was the first real blockbuster from the Wellcome Foundation – a true heir to the founder’s Big Idea. Although rooted in the inspiration of the company’s US science chief Dr George Hitchings (who later won a Nobel Prize), where it really triumphed was in its packaging and marketing. Just like the magic ink.

Septrin is actually two drugs put together, both of which inhibit folic acid synthesis. One, trimethoprim, was patented by the company in 1957. The other is an obsolescent sulphonamide (called sulphamethoxazole) from the Swiss drugs giant Hoffman-La Roche. Tabloided together into a single pill, their worldwide gross is more than $5 billion.

But for nearly all infections, the drugs didn’t need combining. There was no advantage in taking two. Reports in the medical literature said so plainly, beginning in 1973. The journal Chemotherapy said so. The Annals of Clinical Research said so. So did the Journal of Clinical Pathology. In 1978, the British Medical Journal said so. And in 1980, a team declared in The Lancet that, compared with Septrin “single therapy with trimethoprim has the advantage of smaller tablets and fewer side effects, and it is cheaper”.

But in the 1960s, Roche was a major company and the late Henry’s empire was still small. So a deal was done to piggyback the drugs together, and to market them, beginning in 1969, as possessing the magic ingredient of “synergy”.

It was classic Henry Wellcome, all set out in the will: the house style and corporate culture. Remembering the success of his Tabloid promotions, the founder had advised his successors in his memorandum: “I consider it in the best interests of the several industrial organisations and of all concerned that the publicity, advertising and other propaganda shall be steadily increased as the output is increased in volume and in profits.”

With Septrin, moreover, his ideas were rolled-out for what was yet to come. The next phase was to tackle moneymaking another way: instead of selling more drugs by getting people to take two, selling more drugs by doubling the numbers who were considered to be suitable consumers. This was the story in the 1980s and 1990s with Zovirax and AZT.

At the level of science, Zovirax’s compound, acyclovir, was even more of a landmark than trimethoprim. Synthesised in Wellcome’s American labs in 1974, it was the first significant treatment ever licensed that could safely block viral replication. Although it did not cure the often recurring herpes attacks, it showed that, in principle, viruses, like bacteria, could be chemically blasted without killing the patient.

Since Zovirax was launched in 1982, it has saved lives and relieved distress. Particularly in intensive care, Aids and transplant surgery, where immune suppression is a critical problem, the inhibition of the herpes simplex virus has proved to be a godsend. But the volume of sales such patients generate is by no means on blockbuster scale. The real opportunities are for mass-market conditions – and for those the situation is less clear.

“’You have genital herpes’ can be a hard line to follow. We can make it easier for you to help.”

This was the theme of advertising to US doctors, promoting acyclovir in 1993. But, despite such pitches, the wider benefits of the drug were not quite what many supposed. For genital herpes, it can reduce the symptoms, but research suggests sufferers continue to be infectious. With acyclovir cream, used for common cold sores – most often caught from kissing – research has found that its plain cream base is as effective as the actual drug. And a Wellcome initiative to sell acyclovir for chickenpox, has been dubbed a pointless therapy.

AZT, meanwhile, (branded “Retrovir”) was a breakthrough upon its launch in 1987. But, unfortunately, its benefits have remained mired in controversy, due to massive, and inappropriate prescribing. First synthesised in 1964 as a candidate treatment for cancer, it was abandoned for that purpose because it proved too toxic, sickening patients before zapping their tumours. But for people with Aids, in short sharp courses, it gave a few months of respite.

But, true to Henry’s will, the company went further, seeking its prescription to HIV-positive people who had no symptoms of disease. In a worldwide campaign, medical journals were stuffed with advertising and promotional articles, doctors were bombarded with calls from sales reps, and perhaps most worryingly, patients were targeted with what seemed like objective advice:

“People are finding ways to stay healthier, strengthen their immune systems,and develop positive attitudes. They’ve found that proper diet, moderate exercise, even stress management can help. And now, early medical intervention could put time on your side.”

The potential market was one hundred times bigger than possible sales for full-blown Aids. But even as the campaign to push the drug raged, scientists were disputing this strategy. In April 1994, the medical journal The Lancet published a giant European study which found no evidence of such life-prolonging benefits.

Is the Wellcome empire worse than other drug businesses? No. That isn’t the point. What Henry Wellcome bequeathed was not more of the same, but a template which the others have employed. It’s no exaggeration to say that, with his partner Burroughs, he pioneered putting marketing above medicine.

If the founder’s ghost still wanders 183, you would have to wonder in what frame of mind. Is he is moaning over Syrie and Somerset Maugham, who turned him in on himself? Or is he chuckling over the markets for his empire’s pharmaceuticals that such progressive lifestyles have bequeathed?

![]()

The Moneyspinners

The Sunday Times, 6 March 1994

By Brian Deer

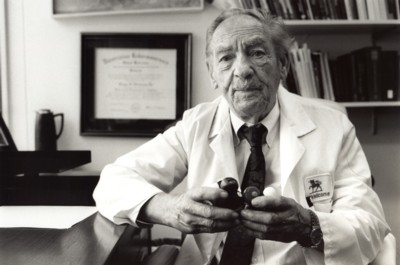

When in 1944 Gertrude Elion joined the laboratories of the New York-based Burroughs Wellcome Company, its executives only reluctantly accepted her, as a favour to their chief biochemist. “Okay, there’s a war on,” they conceded, perusing the then-26-year-old’s details; but she had recently been flitting from job to job and had not got her doctorate. In addition, they declared, she was female and would therefore, sooner or later, quit science for marriage and a family.

Fifty years later, generations of the drug firm’s management have swept in and later cleared their desks. And the United States’ operation has moved south to Durham County in North Carolina. But Elion is still firmly on the Burroughs Wellcome payroll, and shows no sign of quitting. Scattered about her office in the British-owned company’s headquarters, she displays 18 (honorary) doctorates, a Nobel prize for medicine, and square metres of other distinctions. She has also confounded her long-gone critics by only ever being married to her job.

She did, however, help to start a family – though not of the usual kind. With the man who hired her, Dr George Hitchings, her labours in the laboratory spawned a string of medical products. Without them, the Wellcome drugs empire, started by the late Sir Henry Wellcome, might have gone bust decades ago.

There was 6-mercaptopurine, the first treatment for leukaemia; azathioprine (or Imuran), for use in organ transplants; allopurinol (Zyloric or Zyloprim), for gout; and pyrimethamine (or Daraprim), an anti-malarial. There was trimethoprim (part of Septrin, Septra or Septran), an antibacterial; and acyclovir (Zovirax), the most effective treatment for herpes. These drugs then paved the road to Wellcome’s AZT (Retrovir), for people diagnosed with Aids.

The scale of her achievement in half a century of research is hard for nonspecialists to grasp. Both Elion and Hitchings – now aged 89 – who shared the 1988 Nobel prize for medicine with Britain’s Sir James Black, often find it best to explain in anecdotes the difference their drugs make to patients.

Recently, Elion (“Trudy” to her friends) got a letter from a mother whose child’s life was saved by a course of acyclovir. Hitchings – who thinks he met Henry Wellcome in the 1930s – looks back to the decade that followed, when mercaptopurine gave remission to a woman with leukemia, who had a child before she relapsed.

But you won’t get much help from either inventor in ranking their inventions’ importance. “It’s like being asked to discriminate amongst your children,” Elion says. “It’s very difficult to say that mercaptopurine was more important than Imuran, was more important than allopurinol. Or that acyclovir was more important than all of them. Because they came at different times. They were for different uses. And each one in its own time was kind of a revolutionary drug.”

Viewed by the accountants and salespeople at Burroughs Wellcome’s parent company in London, however, some look better than others. Together, a quartet of billion-dollar drugs – allopurinol, Septrin, AZT and acyclovir – have turned Wellcome from what was essentially a small-time marketing outfit at the time Elion joined it, into one of today’s pharmaceutical giants. Yielding more than half the company’s £2 billion sales revenue last year, they have transformed it into one of the few world-name corporations still controlled from the United Kingdom.

Besides filling the coffers of the parent – trading, confusingly, as the Wellcome Foundation – the same four products have also crammed the kitty for the yet mightier Wellcome Trust. This body – a registered charity set up under the terms of Henry Wellcome’s will – controls the company with 40% stake, and is the richest medical research fund in the world. With assets of more than £10billion, it funds work by thousands of doctors and scientists.

The trust gives out more than £400m a year, with the biggest awards in 1993 to specialists working in neurosciences, molecular and cell biology, physiology, pharmacology, infectious diseases and immunity. Its American equivalent, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, also makes major grants, mainly to support pharmacology research and foreign travel by favoured individuals.

During the 1970s and 1980s (when the charity still held all of the company’s share capital), it was mostly profits derived from Elion and Hitchings’s allopurinol and Septrin which flowed through the trust and the fund. Then, unlocked in record-breaking stock market flotations in 1986 and 1992, the growth-spurts of their children AZT and acyclovir became the source of windfall cash.

*****

Confronted by Elion’s world-weary eyes and no-nonsense charm, it is certainly ill-mannered, and perhaps even cruel, to say anything ill of her offspring. In stories of a childhood in Brooklyn, she talks about how a favourite grandfather died from cancer, propelling her into a lifelong quest. It is a similar story with Hitchings, who grew up on the Pacific coast of Washington state, and was 12 when his father died. For some 45 years this pair shared a lab, sometimes seven days a week.

But, as was revealed last week in the first part of our investigation, research suggests that three of Wellcome’s big four products – the antibiotic Septrin, the Aids drug AZT, and the herpes treatment acyclovir – have all been promoted by the company’s marking people beyond the best medical opinion. Much of their yield has come from prescriptions to patients who might not need them, or for whom they were unduly dangerous.

It can take years for independent investigators to get the measure of a drug’s benefits and risks. So it is the older product, Septrin (also branded as Bactrim), that has prompted the most forceful concerns. In this antibiotic, a relatively safe and effective compound called trimethoprim (invented by Hitchings) was mixed with a more dangerous, and largely redundant, sulpha chemical (sulphamethoxazole), in a controversial marketing deal.

Since its launch in the late 1960s, research suggests that this combination drug may have been associated worldwide with what could be thousands of deaths and injuries. Even during the past week, people have contacted The Sunday Times to talk of their personal misfortunes.

One mother complained that her four-year-old son had been rushed, close to death, to hospital after taking Septrin for a chest complaint. Another user recounted how her life had been “ruined” from a chronic syndrome that set in immediately afterwards. Meanwhile, Wellcome’s solicitors said that our reports “appalled” their clients, and that they were considering their legal position.

The fourth big earner – the gout drug allopurinol – was not examined in last week’s reports. It too has greatly helped a relatively defined group of patients, but was marketed far beyond its best usage. Like the others among Elion and Hitchings’s creations, it reveals a system in which some patients can be prescribed medicines for whom advantages and dangers may be skewed.

Gout is a disease for which there is still no cure, caused by an excess of uric acid in the blood (“hyperuricaemia”). It mostly shows in old people, when it super-saturates tissues, sometimes causing swellings and pain. In its chronic state, the acid forms crystals – particularly in the kidneys and joints – producing deformities and a condition like arthritis.

Elion and Hitchings conceived allopurinol almost by accident, while searching for cancer treatments. But in 1956, they stumbled on its effects, and so a gout drug was born. It was the kind of mix’n’match discovery that was common in those days, and which even now makes Hitchings smile.

“We said: ‘Now we’ve got the drugs,”‘ he chortles, during an interview in his office, along a wide, carpeted corridor from Elion’s. “‘All we’ve got to do is find the diseases that go with them.”‘

When allopurinol was first marketed, in 1963, it seemed like an unqualified success. Many thousands of gout sufferers (Elion included) found that the drop it brought to uric acid levels meant that the disease, at last, became bearable. Although reliance on it may have distracted from much-needed diet and lifestyle changes, it at least relieved symptoms for most users.

But even the commonest drugs are not free of downsides, and it soon became clear that some patients on allopurinol found that it caused rather than relieved gout symptoms. Side-effects, meanwhile, could range from mild skin rashes to fatal blood disorders and a hypersensitivity syndrome.

In 1970, The New England Journal of Medicine – the world’s top medical publication – reported the first strongly-linked death. It was of a 72-year-old man who had been diagnosed with gouty arthritis in 1944, but who was stable until discovering allopurinol.

By January 1986, 22 deaths linked with the drug had been published in the medical press – and were reviewed in the journal Arthritis and Rheumatism. This noted “significant morbidity and mortality associated with the allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome,” and warned doctors to temper their prescribing.

In the intervening years, however, Wellcome had promoted the drug heavily, with advertising and sales visits to doctors. These advocated its use not just for people with gout, but also for those with only raised uric acid levels – so called “asymptomatic hyperuricaemia”. In the same way that the company was later to argue that AZT should be used to prevent Aids developing in HIV-positive people, rather than merely for treating the sick, allopurinol was prescribed to the much greater patient numbers who were only predisposed to gout.

“Remember Zyloprim the original (allopurinol),” was one popular advertising campaign for doctors, which kept the complexities to mandatory small-print. Another – which ran at the front of the Journal of Rheumatology continuously between 1974 and 1986 – declared bluntly: “In hyperuricaemia or chronic gouty arthritis, Zyloprim.”

Although such ads may have been technically accurate, the increased consumption that they encouraged inevitably raised the numbers exposed to side-effects. While most patients handled allopurinol well, studies showed that about 2% experienced adverse events, with one hospital survey finding that, of every 260 patients treated, one had a life-threatening reaction.

Other research showed that most of those who suffered or died, should not have been taking the drug in the first place. “The vast majority of patients, both in our series (7 of 8), and reported in the literature (51 of 59), who developed allopurinol hypersensitivity, did not have proper indications for receiving the drug,” reported researchers in the journal Arthritis and Rheumatism. “Serious and often fatal allopurinol hypersensitivity is a high price to pay for inappropriate therapy.”

*****

No blame attaches to Elion for drug promotion – and she says she doesn’t even use allopurinol for her own gout. “That aspect of the marketing, I have nothing to do with,” she explains. “Once the thing is established, sometimes they do things that are commercially feasible, and commercially important, and perhaps not medically important. And that’s a decision that I don’t have to make.”

But exactly who is responsible isn’t easy to pin down. In London, Wellcome points to doctors and regulators who prescribe and rule on proper usage. Whether you talk with the commercial Wellcome plc, or the charitable Wellcome Trust, they take the position that it is neither company nor charity which decides on who gets what.

It is not surprising that they speak as one: it is what the founder, Henry Wellcome, had intended. In his will documents, filed in 1932, he stressed his belief in a co-ordinated approach, with marketing the name of the game.

“It is my special desire that there should be no material reduction in the proportional expenditure for publicity and other forms of propaganda of the several organisations,” he stipulated for his posthumous empire. “As I wish my trustees and the directors continuously to develop and increase the output and sale of the products of the industrial organisations of the Foundation throughout the world. The consistent pursuance of this policy will ultimately result in greatly increased profits.”

But today the trust sponsors some of the most prestigious medical departments. It has an advisory system of more than 3,500 doctors and scientists. It owns one of the finest medical libraries and on-line retrieval systems. It has a multi-million pound research institute at its Euston Road headquarters. Its seven-person governing board includes a doctor and four professors. If it cannot evaluate its medicines’ profiles, then it is hard to know who could.

In a structure that distributes a share of its profits to researchers, moreover, there may be conflict of interest anxieties. When asked whether grant-seeking experts may feel inhibited from criticising Elion and Hitchings’ big four products because of the organisation’s enormous reach, Dr Bridget Ogilvie, the trust’s director, did not refute the suggestion. She declined to comment.

This issue is sensitive, touching on ethics and propriety in an ever-more competitive world. Increases in research costs, and tight controls on public spending for science, mean that the trust is bombarded with requests for sponsorship – two thirds of which it refuses. Last year, even on the British government’s Committee on the Safety of Medicines, 19 of the 21 members either worked in institutions which received Wellcome money, or were granted a share of it themselves.

The potential for a ménage between company, charity and experts, is a worrying feature of the founder’s legacy. Collusion was central to Henry Wellcome’s thinking, with his will documents noting that some granted research money would produce “much of purely technical interest,” but that even this “should also contribute to the discovery of remedies and curative agents and new methods of treatment which may be of practical interest and importance to the industrial organisations of the foundations”.

In the United States, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (of which Elion and Hitchings were for many years directors) has kept particularly close to this prescription. One of its biggest recent grants is a $350,000 award for “innovative methods in drug design and discovery”, which in 1992 went to Dr Susan Amara in Oregon. Her work relates to brain chemicals which, according to the fund “may help physicians combat cocaine addiction”. Meanwhile, Wellcome has a drug, bupropion, “undergoing clinical trials in the USA for the treatment of cocaine addiction”.

In Britain, cross-fertilisation between company and trust has reached even the highest levels. One distinguished figure, whose profile has risen with Wellcome’s, is Sir Roy Calne of Cambridge University, one of the most accomplished transplant surgeons. As a young man, he helped Elion and Hitchings to develop azathioprine and, in the years that followed, was endowed by the charity with grants, research help and expenses.

Another example of how working with the company can be followed by trust support involves two professors: John Stenlake of Strathclyde University and James Payne of the Royal College of Surgeons. Both were key figures in developing atracurium, a top-selling Wellcome muscle-relaxant. Stenlake received trust grants for his work between the late 1960s, when atracurium’s development began, and the mid-1970s. Payne got assistance in the early 1970s and the late 1980s.

Another instance recently is the case of Herman Waldmann, professor of therapeutic immunology at Cambridge, and a fellow of the Royal Society. With financial support from the trust, he advanced a revolutionary Wellcome product, Campath, the world’s most developed monoclonal antibody. After assigning it to the company, he became an adviser to the charity and sought to obtain further sponsorship. This, however, was blocked last year – he believes on the advice of lawyers.

Nobody suggests impropriety by these respected figures, who are bound to seek funding where they can get it. And the trust would flatly deny that there is any quid pro quo when it offers its financial support. But it is clear that at least some collaborators hope for the trust’s rewards after furthering the company’s goals.

The money they get, of course, rarely goes into their pockets. The trust’s help is to support research. But it is rarely cash in the bank that wins the hearts of people of the highest standing and influence in science. More often they are driven to advance medical progress, or to win peer-recognition. It’s a popular misconception, Elion says, that people like herself are primarily driven by their wallets.

“They think that we get some personal monetary reward out of it, and that really isn’t what we want,” she says of the many who misunderstand this point and assume she must be rich. “What we want is a chance to do research. A chance to, you know, get some additional people in our departments, and so on.”

*****

While it is the trust which has handed out most of Wellcome’s money, the kind of opportunities to which Elion is referring can also come directly from the company. Both the Wellcome Foundation and Burroughs Wellcome in the US make major contributions to the medical money-go-round that is now a mainspring of the pharmaceutical industry.

During the last five years, Wellcome has courted particular controversy over its financial interventions in the field of Aids. People with this condition will often not only use AZT, but may also take acyclovir and Septrin as well: generating millions in profits to distribute. Recipients have ranged from the mighty US department of health ($5m), to countless small-time self-help groups.

Much of this money has created a climate to support trials of Wellcome products. In an American coast-to-coast test which won AZT its licence in 1987, for instance, one hospital, Massachusetts General, received $140,000 for data on just 19 patients. Other participants were also generously rewarded – and far from such payments guaranteeing good work, inspectors have discovered many flaws.

Another example concerns one of the most powerful medical figures: Dr Samuel Broder of the US National Cancer Institute. Broder is the person most associated with AZT’s approval, and, crucially, was supported by Burroughs Wellcome. Although the money went to his laboratory, and not into his pocket, he accepted $55,000 at the time the company’s product was under federal review.

Surprisingly, Aids activists, including the militant group Act-Up, have also been backed by the company. Among the group’s many high-profile protests in the epidemic’s early years, Act-Up had even broken into Wellcome’s US offices. But in July 1992, only weeks before the trust floated a huge block of shares, Act-Up leaders appeared at a New York press conference to shake hands and accept $1m. Meanwhile, the British company spent £60,000 last year flying Act-Up supporters to a conference.

Even journalists and politicians are not overlooked, as Wellcome’s founder’s dream plays out. Writers are often helped to attend meetings in foreign locations, while even the European Community held a parliamentarians’ conference last year that was sponsored by the Wellcome Foundation.

Such techniques – now common throughout drug-based medicine – provoke mirth from close observers. Sir James Black – Elion and Hitchings’ fellow Nobel prizewinner – smiles at mentions of the Wellcome Foundation, for which he used to work. “The industry as I’ve seen it, I think, takes the view that marketing drugs is the same as marketing anything,” he says. “The promotional methods used by the pharmaceutical industry are no different from the promotional methods used in any other branch of the chemical industry.”

Black addresses an issue he thinks the public still under-appreciates: the pressure of commercial imperatives. Wellcome’s main board comprises much the same people who might run a bank or an oil company – and who do their job in much the same way. The difference lies in the reputation of medicine and science to assure us that they do their job well.

There have been no doubts about integrity at the top. Roger Gibbs, the chairman, has had wide business interests, including the London Clinic and the Arsenal football club. Another board member, Sir Peter Cazalet, is a former oil man and a prominent industrialist. But, in the legacy and structures set up by Henry Wellcome, the profit-sharing scheme, that continues to grow, may have acquired a life of its own.

Trying to control this has proved endlessly difficult, creating difficult management decisions. At least until 1984 (when such information ceased to be available), the trust invested in the British American Tobacco Corporation, as well as a string of breweries. Possibly good investments, but not free of controversy for a business which showcases support for health.

More important than such embarrassments, however, is how the trust and the company may be preparing for years to come. Both are deeply involved in biotechnology and genetic engineering – areas where error, or an excess of marketing, could lead to a catastrophe. As Wellcome’s empire grows, through its tax-exempt charitable arm, and the company’s drug development programme, the medical money-go-round may lead to error that puts humanity itself into a spin.

Some doctors and scientists look forward with hope. Elion glances back with nostalgia. “When we first had people working on 6-mercaptopurine, allopurinol, Imuran, we didn’t pay one cent for those studies,” she remembers. “We didn’t influence them in any way.”

No doubt if her offspring had been children instead of drugs, she would have warned about candy from strangers.

Note: Vagaries of editing mean this version is slightly different in places to what was printed in The Sunday Times. The second part of Hard Sell, referring to Elion and Hitchings, appeared under the heading “The Moneyspinners”

MORE TOPICS:

Bactrim-Septra: a secret epidemic

Research cheat Andrew Wakefield