Reprint

![]()

Nature’s prey

The Sunday Times Magazine

March 9 1997

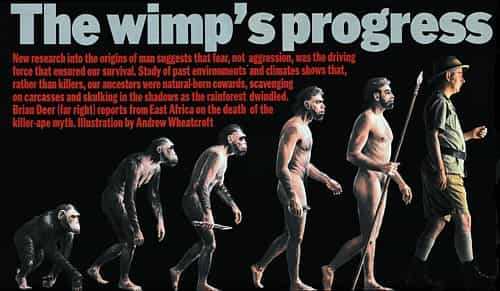

New research into the origins of man suggests that fear, not aggression, was the driving force that ensured our survival. Study of past environments and climates shows that, rather than killers, our ancestors were natural-born cowards, scavenging on carcasses and skulking in the shadows as the rainforest dwindled. BRIAN DEER reports from East Africa

It might sound to you like a dumb thing to say, but when I finally got my head round the origins of our species, the story made me cry. It was a Sunday morning at the time, and I was chasing the subject on Tanzania’s Serengeti Plain in a rented Hyundai four-by-four. Clouds of ochre dust boiled behind the vehicle. Zebra and gazelle leapt up left and right. And a compass needle bounced on the passenger seat beside me as I sped across the roadless terrain. There was no other person as far as the horizons: if the car broke down I might have starved. And then weeks of research fused together with the landscape, bringing tears to my sunglazed eyes.

The funny thing was that before I checked it out, I had assumed all that corny “Garden of Eden” stuff was on videotape, in the can, cut and dried, decided. After all, who can’t recall some celebrity anthropologist strolling towards a television camera, holding forth about how Homo sapiens sprang from Homo erectus, which, in turn, was begat by Australopithecus, which, a very, very, very long time ago hung around in the trees like apes? It has been 6 million years since we split from the chimps. Your first thought isn’t breaking news.

All the punditry I’d seen on the subject, moreover, was no reason to act like a wimp. By most accounts, humanity’s triumph over the animal kingdom was a spiteful business, as Charles Darwin’s principle of natural selection was played out between competing bands of proto-humans, or hominids, in old world locations such as this. Even schoolkids know how our descent from the trees marked the start of our use of tools and weapons – and how the most ruthless hunters and killers amongst us proved the fittest and therefore survived.

This account is mostly the legacy of the science of palaeontology – the finding and making sense of fossils. For the best part of the twentieth century, a steady accumulation of fossilised hominid fragments have been indexed and displayed in museums around the world, like keyholes to peer into Eden. And with little else apparently surviving decay and the crushing weight of millions of years of rock-forming debris, they have taken centre stage in our picture of human origins, helping to shape our image of ourselves.

To date, East Africa has provided most of the key specimens – with the most celebrated site for headline-grabbing finds not far from my route that Sunday. The parched Olduvai Gorge, the so-called “Grand Canyon of evolution”, and since the 1930s location of world-famous bone hunts by the white Kenyan adventurers Louis and Mary Leakey, was just 40km south-east of my route, back towards the Ngorongoro Crater. I had spent a bit of time there, among wind-eroded sediments, where for decades they had scoured the ground.

It was a guy called Dr Raymond Dart, however, who was the father of this line of inquiry. Before World War II, as a professor of anatomy at South Africa’s Witwatersrand University, he became renown for bringing to the public’s attention a string of 3m-year-old Australopithecus finds – a so-called “missing link” genus he named (It’s Latin for “southern ape”). And it was he who forged the now-commonplace assumption that the reason why we evolved from our tree-swinging cousins was our forebears’ relentless violence.

He first staked this claim in 1953 in a paper titled The Predatory Transition from Ape to Man which, although read by only a few specialists, did nothing less than to trigger a science-based movement turn the century’s intellectual tide. Published in the obscure Miami-based International Anthropological and Linguistic Review (whose editor sheepishly claimed that Dart was referring only to “the ancestors of the modern Bushman and Negro, and of nobody else”), in 1961 his ideas reached the public via a Chicago scriptwriter, Robert Ardrey, who turned Dart’s conjectures into a 350-page best-seller, catchily titled African Genesis. As I sped across the Serengeti that Sunday morning, it lay caked in dust under my compass.

“What Dart put forward,” Ardrey explained, “was the simple thesis that Man had emerged from the anthropoid background for one reason only: because he was a killer. Long ago, perhaps many millions of years ago, a line of killer apes branched off from the non-aggressive primate background. For reasons of environmental necessity, the line adopted the predatory way. For reasons of predatory necessity, the line advanced. We learned to stand erect in the first place as a necessity of the hunting life. We learned to run in our pursuit of game across the yellowing African savannah.”

This powerful notion was soon grabbed by popular zoology when in 1967 a London Zoo curator and children’s television presenter, Desmond Morris, broadened its appeal in another best-seller, Naked Ape, reprinted a dozen times in 18 months. And then, in the ideologically pivotal year 1968, Dart’s thinking reached a truly mass audience in the opening sequence of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, listed by Variety magazine as one of the top 50 moneymaking movies ever.

I remember my father taking me to see a rerun – and Hal, the computer, left barely a trace on me compared with that sequence projected in the dark. Under eerie red skies on a barren landscape, and following a brave caption THE DAWN OF MAN, a bunch of guys in gorilla suits hop about grunting, and foraging for berries and roots. But then one grabs a zebra femur and (to the majestic swell of Richard Strauss’s Thus Spake Zarathustra) begins pulverising stuff in slo-mo swings, with a crazy kind of stare its eyes.

Before this multimedia blitz for Dart’s hypothesis, science-based debates on the origin of our species had been short of an epic narration. While evolutionary theory back to Darwin suggested that we must have shared ancestors with our three fellow ape survivors – the chimpanzee, gorilla and orangutan – there was no convincing, much less agreed, hypothesis as to why this should have occurred. The complexity and apparent purposefulness of human tissues, nerves, muscles and so on seemed to many improbable features to be merely the products of random mutations.

In what Ardrey dubbed “The New Enlightenment”, it was Dart who stepped into the post-Darwin void to displace the hand of god. “Australopithecus lived a grim life,” the anatomy professor wrote, graphically sketching his portrait of Adam and Eve. “He ruthlessly killed fellow australopithecines and fed upon them as he would any other beast, young or old. He was a flesh eater and as such had to seize his food when he could and protect it night and day from other carnivorous marauders.”

In the late 1960s, as the liberal civil rights, antinuclear and Vietnam War movements, reached a crescendo, conservative ideologists seized on this hypothesis, which seemed to point in a welcome direction. Just as Siegmund Freud had stirred resonances in the century’s first half by revealing the child who lives within us, so the “killer ape” hypothesis beckoned in the second half, suggesting that such a child, if it survived at all, rode on a wild animal’s back.

What clearer precedent for, say, the manifest destiny of white men to rule, or the unfairnesses of the free market, than a scientifically-proven and commercially-successful theory that predatory aggression was no mere vice, but the driving force of who we are? “Far from the truth lay the antique assumption that man had fathered the weapon,” wrote Ardrey in full-blooded scriptwriter mode. “The weapon, instead, had fathered man.”

That it’s a cruel world, after all, didn’t you know, is a lesson from our relatives in the wild? Even before Dart’s message became entrenched as orthodoxy, Louis Leakey had in 1957 installed Jane Goodall, a 23-year-old secretary from England, to report on the common chimpanzee population at Gombe River – maybe a day’s drive to my south-west, near Lake Tanganyika. In what was considered science for the period, the former waitress had arrived at Gombe, ordered the grass cut and dumped vast quantities of trucked-in bananas, before documenting a fractious pandemonium of the apes. Soon she was writing about vicious hunting parties in which our cheery cousins trapped colubus monkeys and ripped them to bits, just for fun.

Dart, the Leakeys, Goodall – the lot of them – had, of course. studied their specialities for decades. I, meanwhile, was merely passing through, little more than a Sunday afternoon driver. But as the zebra and gazelle scattered around me that morning, I reconnected with a feeling that I had been getting for some time: that the killer ape story was fiction. Like with the guy who more recently wrote a book called The End of History, claiming that human organisation had achieved its ultimate manifestation (in American capitalism), it was a mixture of wishful thinking and catchy formatting, primarily intended to sell.

I had felt something was amiss even before arriving in Africa, but after talking with a new generation of scientists from the United States, Europe and Australia, and mugging-up on shelvesful of the latest research in the library at Kenya’s national museum in Nairobi, I had found new evidence, refuting Dart’s narrative. And as I had travelled around the Great Rift Valley of east Africa, looking at sites where research was happening today, it seemed to me that his tale was little more than a thriller – understandably attracting scriptwriters and directors.

In a sense, you can disprove Dart by looking into yourself. But new, more objective, methods have emerged to reanalyse the hard surviving evidence of our past. With Dart and Ardrey long-dead, the Leakey dynasty losing influence over the African sites, and even Hyundai four-by-fours available for hire, archaeologists, geologists, climatologists, botanists, geneticists and all kinds of scientists, using revolutionary investigational methods, are breaking into the domains of the old white adventurers. And they are finding new keys to Eden.

*****

The night before my drive across the Serengeti, I had an amazing dream. As it happened, it was prompted more by the side-effects of the anti-malarial mefloquine than by anything Freud would have recognised, but the form it took was to transport me back to the gates of just such an Eden. Knuckles swinging like an Australopithecus, through a dim, humid forest, I was trying to find a tree within which to take shelter from a driving, monsoon rain. A dense green canopy filtered the light, and from beyond it came the ominous dull rumble of thunder, which eventually woke me up.

If the drug was the trigger, then the mood had been set by a chilling bedtime story. On Saturday afternoon, I had descended alone into the Ngorongoro crater, climbed from the Hyundai to photograph hippos, and was confronted by an adult animal at 20 feet. Figuring – ever the liberal – that I was disturbing the wildlife, I walked slowly back to my car. But over dinner, a celebrity American photographer, Peter Beard, graphically explained that I was a lucky man indeed to be alive to pass him the yams. The kiddies favourite soft toy killed more people than crocs or cats, he said, and had this one seen a glimmer of water behind me, it would have run me down, shaken me to death and pounded my car to scrap.

So I was surging with medicine and the residue of terror when the dream formatted this story. At the heart of the new origins research has been a amazingly recent acceptance among anthropologists that humans were created by, and not merely in specific ecological settings – most notably the great primeval rain forest which once swathed the planet’s tropics. To fathom us, the new thinking goes, you don’t just go hunting skulls, or watching chimps, you have to start afresh by considering precisely the landscape that had surfaced in my dream.

“If you want to understand why human evolution took the course it did, then you have to understand how hominids articulated with their environment,” Tom Plumber, a palaeoecologist from the University of California, Los Angeles, working in western Kenya, had explained to me the previous week. “They weren’t evolving in isolation from everything else. They were part of dynamic ecosystems, which were much like ecosystems that we see today.”

By this view, only once we have looked over the Garden of Eden’s flora do we zero-in on the two-legged mammals. Although the fossil record is as full of gaps as 36 exposures of the D-Day landings, we can tell from bits of skull and bone that the rain forest was home to so many types of monkey (which ran horizontally through the trees), apes (which clambered upright, or swung) and Dart’s australopithecines (which analyses of the famous Lucy skeleton from Ethiopia suggest slept in the branches, but waddled awkwardly on the ground), that the features of each shaded into the next: a jumble of evolutionary traits.

Even using such names for countless related hominids creates a misleading cartoon reconstruction, but accepting Australopithecus as my dream’s knuckle-swinger from before The Dawn of Man, and Homo erectus as the first step after the sunrise (say, 2-2.5 million years ago), then understanding why one died off and the other took off might explain why in sleep my hands touched the ground and awake they gripped a wheel.

Perhaps another reason for my rainforest dream is that, awake, I kind of envied Australopithecus. Although he got by on a mere 450gms of brains, compared with my possible 1400gms, in the lush, steamy vegetation before today’s Serengeti, he didn’t have much to use it for except eating, sleeping and sex. Males were vastly bigger than females, and would have been able to live much like gorillas do now: keeping harems grouped near their favourite trees, where food was in good supply.

This was California Dreamin’ without the property taxes, and you can bet he didn’t bludgeon his way out. Instead, new technologies, analysing such things as cores drilled from Arctic ice-caps and ocean beds, reveal that between about 2.59 and 1.69 million years ago, long-term climate changes would have shocked Australopithecus like an eight-lane freeway down Main Street. Variations in Earth’s orbit threw the planet into a cooler cycle – cutting atmospheric energy, and therefore rainfall, and causing swathes of the forest to wilt. First, patches of light woodland thinned the lush canopy. Then came grassland, the dry savannah, like parts of the Serengeti on which I drove.

This change in itself had dramatic outcomes as many plant and animal species went extinct. But the environmental engine of our species’ evolution was also moving in another direction. Earth, then celebrating its 4-billionth birthday, was also shrinking, causing its crust to crunch and continents to drift, throwing landscapes this way and that. As earthquakes rumbled around the Pacific zone, a 6,000km fissure tore through east Africa (today’s Rift Valley, from the Red Sea to Tanzania’s Lake Manyara): creating a hotpotch of faults, buckles, domes, basins, and all kinds of contortions in the landscape.

Geological surveys of sediment beds, sometimes hundreds of metres thick, show that, over thousands of years, local climates ebbed and flowed as mountains rose and valleys sank. Lakes became rivers and rivers became lakes, or sometimes both disappeared. Changing rain shadows and drainage patterns turned forests into woodlands and woodlands into grass, and sometimes back into forests.

The result was thousands of micro-environments, each suited to different styles of life. “The eastern Rift Valley and its surroundings had a mosaic of vegetation types not too unlike those of today,” wrote the late archaeologist Glynn Isaac in an essay pasted in my notebooks. “A pattern in which various types of dry thorn savannah and open woodlands predominated, was interspersed with gallery forests along water courses and perennial rivers, and with evergreen forests on the major highland areas. Substantial areas of grasslands occurred on floodplanes and probably on high plateaux. Large tracts of unbroken lowland forest probably did not occur.”

Analysis in this chapter in humanity’s genesis launched the first big challenge to Dart. It has been clear to specialists for at least a decade that the environmental convulsions would have been quite enough to cut the ground from Australopithecus, without any armed New Enlightenment. With its small brain (only about 50gms bigger than a chimp’s) and restricted locomotion, it would, for the most part, have been too stupid to adapt to the stresses of the changes in its habitat.

“The shrinkage of forests at about 2.5 million years ago created a crisis for hominids,” wrote Steven M Stanley, in the journal Paleobiology, which I found on the shelves of the Nairobi library. “Most populations should have experienced greatly increased predation pressure. Many (perhaps most) died out, while others abandoned obligate arboreal activities. One population, whether it constituted a fraction or all of the survivors of the ancestral species, evolved into Homo.”

Ironically, today’s investigations into this transformation are often around sites that the household-name palaeontologists have long since abandoned as barren. At Olduvai, for instance, Robert Blumenschine, professor of anthropology at Rutgers University, New Jersey, is leading a team that is unearthing material that the Leakeys could never have recognised. While the white Kenyans’ primarily focused on finding and ascribing ancient dates to headline-grabbing bone fragments, these new ventures are struggling to reconstruct the landscapes and behaviours that would have been seen nearly 2m years ago.

“So much research in the past has been concerned with finding hominid bones and making a case that they are older or more important than anything else,” Blumenschine told me. “But we are interested in what the hominids were doing and why. Only once we understand that can we seriously start to tackle questions about why modern humans have the peculiar traits that we do. These are the interesting questions, but they have previously been restricted to the realm of speculation and armchair philosophising because the right kind of information was not available from the fossil record.”

Working with scientists from the University of Dar Es Salaam, he is investigating Homo erectus’s takeoff around what was once a salty lake. Unlike traditional fossil-hunting, their studies mean digging in huge areas of land, often far from where bones were found, to cross-relate individual stone fragments, fossilised vegetation, pollens and animal remains, past geology and geography, and other clues to what life was like. These are then combined with studies of landscapes around the Rift Valley today.

With similar work at other sites, this method is firstly painting a picture of the end of the rainforest Eden. Among the mosaic of new environments, the most promising sported galleries of acacia, which lined streams and dotted the flood-plains of fluctuating lakes. Rainy seasons spawned short-lived herbaceous plants, but otherwise the ground beneath the trees was bare, and woodlands were surrounded by open grass, only a little more fertile than today.

The next task has been to decipher what was going on in such transformed settings. Enough bone fragments have been found at some east African sites to show that, far from killing each other off, at least three radically different kinds of hominid lived in close proximity for more than a million years. Although Australopithecus’s rain-forest harems were wrecked by the need to forage further afield, it clung on in the woodlands until about 1.2m years ago, still sleeping in the trees. And overlapping it in time and place were the creatures evolving into Homo erectus, which spent most of their lives on the ground.

Elementary theory explains the spark for the transition. “At the genetic level, evolution occurs by accumulated substitutions of one nucleotide by another in the DNA of the organism,” is how a 1995 paper in Science puts it. “Nucleotide mutations arise with constant probability, but most are lost by chance shortly after their origin. The fate of the rest depends on their effects on the organism. Many mutations are injurious and are readily eliminated by natural selection… Other mutations are favoured by natural selection because they benefit the organism.”

Some such mutations would have accomplished a task that every parent today gives thought to. By comparison with our ape cousins, human babies are, in effect, born prematurely, with almost chimp-small brains which then grow at foetal rate in the first twelve months after birth. This unique feature reconciled the narrow maternal pelvis with the big head that was needed to be smart. Whose nucleotide mutations got them there first will never be known, but it was the next step on our path from the forest.

*****

About the time my father took me to see Kubrick’s movie, Desmond Morris fronted a TV show, Zoo Time, which, as I recall, included chimpanzee tea parties, in which the animals were dressed in clothes. In his book, Naked Ape, Morris was equally at one with the times in synthesising Dart’s theory with the ape observations of Jane Goodall – and later with those of two other disproportionately influential young women installed by Louis Leakey (Dian Fossey, gorillas, and Birute Galdikas, orangutans) – to repackage African Genesis as zoology.

“With strong pressure on them to increase their prey-killing prowess, vital changes began to take place,” was how Morris explained the transformation from Australopithecus to Homo. “They became more upright – fast, better runners. Their hands became freed from locomotion duties – strong, efficient weapon-holders. Their brains became more complex – brighter, quicker decision-makers. These things did not follow one another in a major set sequence; they blossomed together, minute advances being made first in one quality and then in another, each urging the other on. A hunting ape, a killer ape, was in the making.”

Morris’s well-titled book has never gone out of print (or amended to take account of its falsification), but the new investigations in Kenya and Tanzania kick dust in his naked ape’s face. Studies of australopithecine pelvises show, for instance, that upright posture preceded major brain expansion by some two million years, and almost every clue gleaned by every relevant specialist reworking the Leakey’s once jealously-guarded domains shows that, whatever our ancestors did on these landscapes, they certainly didn’t command.

Most critically, new evidence suggests that early hominids, at most, ate meat only as a last resort. Dental studies by an English anatomist, Alan Walker of Johns Hopkins University, have revealed no sign that australopithecines ever consumed flesh, but plenty of it chomping on roots and nuts. And similar studies, combined with laboratory analysis of fossil site debris, suggests that Homo erectus was also firmly vegetarian, although sometimes driven to scavenge dead animals.

“The hunting scenario is now totally out of the window,” said Richard Potts, fellow of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, who is leading large-scale excavations at Olorgesailie in southern Kenya. “There is clear evidence from studying the archaeological remains from early sites – that is, starting from around 2.5 million and especially around 2 million years ago – where we have very nice bone preservation. And we see evidence that early humans were exploiting certain animals, but there is no indication that they were hunting them. There is clear evidence that they were getting the bones and cutting meat off them, and there is clear evidence that they were smashing the bones for bone marrow. But that’s about as far as we can go. The first clear evidence we see of hominids as aggressive hunters is not until very late in the archaeological record: within the last 100,000 years.”

One research approach that has clinched this part of the argument are re-examination of museum fossils previously trayed as hominid kills. Under electron microscopes, it has been possible to determine in what order bones were gnawed at by wild dogs or cats and slashed at with the stone tools of our ancestors. In key locations, these studies suggests that Homo got to animal carcasses after their four-legged rivals – sometimes (evidenced by scrupulous fieldwork) after by pelting dogs with rocks.

Far from the demeanour of Dart’s triumphant hunters, evidence suggests that Homo erectus must have skulked warily among the trees that lined the rivers and lakes – or literally been running scared. Hominids have always been among the frailest midsize mammals, especially when encumbered by babies. For creatures who were smaller and weaker than we are, and with brains upwards of half the size of mine, you need only need to get stuck mud on the Serengeti, as my Hyundai, to know how quiet and scary the savannah gets before a Land Rover arrives to drag you out.

The uncomfortable truth for Dart’s hypothesis was that even Homo erectus, much less Australopithecus, wasn’t ruthlessly killing beasts, “young and old”. Such bloodthirsty pursuits were the other way around: the beasts were killing our forebears. These were landscapes on which heroes died. It was cowards who multiplied.

*****

Beside the few dusty tracks that today cross the Serengeti, you will sometimes see a hyena or two panting in the heat. If you want, you can get out and pet them like house-dogs. And they would happily rip you to shreds. Best stay behind safety glass to coexist with wild animals. Thank god for the automobile.

But now try to think about Homo erectus, plodding across the plain in bare feet. Around 2 million years ago was the period of maximum evolutionary diversity, and while today we have cause to fear the pack-hunting hyena, back then there were at least six species. While east Africa today boasts the serious presence of three big cats – the cheetah, leopard and lion – back then there were ten, some much bigger and uglier than anything a zoo could contain. While the lakes today may boast 16ft Nile Crocodiles, then there were at least four kinds to drag you under, some of them twice the size.

Against such perils, hominids stood little chance once they ventured from the trees’ protection. Little chance, that is, until what many scientists believe may have been the real spur to humanity’s leap forward. Far from the weapon, or even the tool, being the defining moment, if any one thing marked Dart’s “transition from Ape to Man”, it wasn’t predatory aggression, but the first technology – our ancestors’ control of fire.

The champion of this view is the archaeologist Jack Harris, chair of the Rutgers University’s anthropology department, who has worked at sites throughout east Africa, including Laetoli, where Mary Leakey famously found hominid footprints. “I have argued that the earliest human-controlled fire was not related to cooking, but for protecting hominids and for securing a place on the ground,” he told me. “Prior to that, hominids spent a lot of time – certainly sleeping – in the trees. Once they had fire, they could ward off predators such as lions and leopards. It also allowed them to move into new habitats in the more open parts of the landscape.”

Controversially, Harris dates this to 1.6m years ago, much further back than previously believed. Since the 1970s, possible evidence has been collected from a dozen sites, from caves at Swartkrans in southern Africa to the desert of Middle Awash in Ethiopia. But until now all observations have roundly been rubbished by champions of the killer ape. They say that, until the time of the rise of Homo sapiens, our brutish forebears were too dumb and clumsy to accomplish such a complicated feat.

The site deemed proof of Harris’s theory is at Koobi Fora, near Lake Turkana in northern Kenya. On what is now a bleak ridge of eroding sediments 20km from the water, surrounded by a volcanic wilderness, materials from a spot hurried over by the Leakeys more than 20 years ago have been subjected to magnetic mineralogy tests which seem to point to an ancient campfire. Stone implement finds and landscape surveys have shown that this was once a living place for hominids, beside a river lined with acacia.

Controlling fire was a revolution: at last there was safety on the ground. Its warmth allowed rapid migration northwards and to higher altitudes. It provided light, thus extending the day. And as a focal point for sharing information, such as where berries or nuts had been found, it was also a spur to developing language – then still only squeaks, clicks and grunts. For the lucky line who got the hang of it first, these features of fire would have triggered a massive brain-boost over those left out in the cold.

“It is probably in this context that people started to talk about the day’s activities,” Harris said of what he believes to be humanity’s most transforming breakthrough. “And it changed the biological clock of humans. Prior to that, humans were like other animals, they were restricted by the daylight hours – particularly humans, who have developed no special adaptation to seeing at night.”

Fire, of course, might attract other hominids, but this might not have been a problem. The revisions that the new investigations are bringing about suggest that strangers would more likely have sparked curiosity and desire than any so-called killer instinct. The latest research shows that the gene-swapping breeding stock that led to modern humans never fell below several thousand individuals: meaning that encounters between different groups must have been enjoyed, as they are among other primate species, as opportunities to exchange DNA.

To the chagrin of the pundits of the 1960s, the same picture is now emerging from our cousins in the wild. Despite reports since Goodall’s stressing the common chimp’s occasional aggressiveness – including a BBC series this summer dutifully dubbing it, as ever, “Man’s closest relative” – zoologists now believe that it is the bonobo, the misnamed “pygmy” chimpanzee, which has remained more like the original stock from which Australopithecus – and we – evolved. Only about 15,000 of these animals remain, mostly deep in the jungle of Zaire.

Although the bonobo’s DNA shows the same differences from humans as the common chimps’s, and it is often of a similar size (but with longer limbs and a narrower chest), the bonobo has rarely been deemed worthy of the discomfort of keeping a watch on its life. But work by feisty Japanese scientists has begun to reveal that, far from it being spiteful or brutish, it enjoys a tranquil life: concluding even the most mundane interactions with indiscriminate collective sex.

“Though there was a clear boundary between individuals of the different groups and they were exchanging loud calls, face to face, no battle was seen,” the Japanese team reported (with appropriate breathlessness) in Primatology Today, after spending months waiting for two bands, each of about three dozen bonobo, to meet for the very first time. “After about half an hour, a female of P group approached a female of E1 group and they performed genito-genital rubbing. Then both groups had a peaceful feeding and resting time.”

Far from the pulverising violence with which Kubrick’s 2001 thrilled the modern public, the accumulating evidence about our ancestors’ behaviour is that the worst hominids were most likely to do was cuddle their rivals too hard.

*****

The tree of our species has many thousands of branches, almost all of which withered and died. To date, palaeontologists have invented countless names for the bone fragments they have pulled from the ground: Homo habilis, Zinjanthropus, Rampithecus, to name but three more. Primatologists, meanwhile, take our origins back past the bonobo, to squirrels and beyond. So, why pick the emergence of Homo erectus from Australopithecus as due any special note? Is there anything, moreover, to be learnt from our ancestors of more than 80,000 generations ago?

“There is a current trend to try to find the origins of the human mind on the Pleistocene savannah,” the dental expert Walker cautioned me. “And I have this perennial question: why then? Why not go back to a fish ancestor, or your grandmother, or a few generations ago. Why pick that as the ancestral thing you are interested in?”

The answer, I suppose, is the speed of the change and the depth of the impact it produced. When Emma Mbua, curator of hominids at the Nairobi museum, showed me a selection of famous skulls, I could see straight away that Homo erectus represented a quantum jump. And measured on the clock of evolution, the 200,000 years or so that it spent diverging from its predecessor was so rapid that it almost makes you want to talk about the day we came down from the trees.

Bones, however, have little to say about the way that their owners behaved – allowing images to be conjured about them that are driven by more recent preoccupations. All of the Australopithecus finds have been in Africa (the latest in Chad) and, until Homo erectus specimens turned up in Asia, fossils were exclusively retrieved by white adventurers in some past or actual European colony. Dart, an Australian working in Johannesburg, made his name during apartheid’s construction. The Leakeys have been prime exponents of white settlers controlling the sites. Even American expeditions in Ethiopia have had a peculiarly imperialist feel.

The killer ape narrative appealed to such folk, for whom the most sophisticated scientific techniques were deployed on fixing their beloved Land Rovers. It was almost as if through palaeontology they felt they could prove objectively that their kind’s supremacy was historically preordained. If old Australopithecus murdered his way out of the trees, it could be argued, how natural and welcome is civilisation’s advance to the polite domination of today?

It was Ardrey, once more, who got the words down – and in whose footsteps I might almost literally have trod on my journey around the sites. The fossil hunters and zoologists were like two “wings” of a “revolution”, he wrote, which dovetailed into a third: “The African independence movements are rapidly converting a continent into something approaching a political state of nature, where primitive human behaviour may be observed not as we should wish it to be, but as it is.”

Attitudes are changing, however, and science is mirroring that. In the same cultural shifts that see aboriginal peoples probed for ancient wisdoms, so Homo erectus is being rehabilitated as something more than a beast. While lonely skulls and stone tools once stressed individualism, large-scale land surveys and evidence of fire now point to a community life. And we now see that it was not aggression, but fear which dominated our earliest lives. Fear, which a philosopher might see as the source of all human evil, is the default emotion of our evolutionary line. It just never went away.

That archaeology and other sciences should now offer us such notions, may say as much about ourselves today as it does about our ancient past. Hardly more than a generation ago, in the heady euphoria of the booming 1960s, the image of the times was the ultimate weapon: the mushrooming nuclear bomb. In the pessimistic, economically fragile 1990s, another image is taking hold in our collective mind: the secure, life-giving tree.

As our planet’s atmosphere sours, as it did for other reasons before, and the last tatters of the primeval forest are threatened with destruction, maybe we see something of our present predicament in the melancholy, scavenging way of life that Homo erectus really knew. “Humans are losing confidence,” Robert Foley, director of the Duckworth Laboratory at Cambridge University, pointed out to me. “We have started to see ourselves as the victims, rather than the masters, of nature.”

Some sense of that loss was weighing on me when I drove on the plain that Sunday. Our origins, of course, is a story of winners. But my emotion – maybe a genetic vibration – was with all those branches of our evolutionary tree that shrivelled. In the fickle, shifting, African mosaic, there were always more losers than winners. Some perished when their rivers turned to mud and then dust. Others were caught by cats. Some were too hairy to stay cool in the day. Some so brainless they simply got lost.

From the wheel of my red Hyundai, I looked across the yellow savannah that afternoon and felt for a moment that I was seeing this landscape as one of these hominids might have done. I wondered if, two million years ago, as the nutritious, protective forest dwindled to islands in the grass, maybe he and his band had made a break from a patch of wilting, fruitless trees. Thirsty, hungry, confused and frightened, they had set off for the empty horizon in search of food and shade.

But they had started too late, had found no water and as the sun rose above them, they had slumped, defeated, in the merciless tropical heat.

They never fell victim to killer apes. Like us, they were nature’s prey.

MORE TOPICS:

Bactrim-Septra: a secret epidemic

Research cheat Andrew Wakefield