Reprint:

![]()

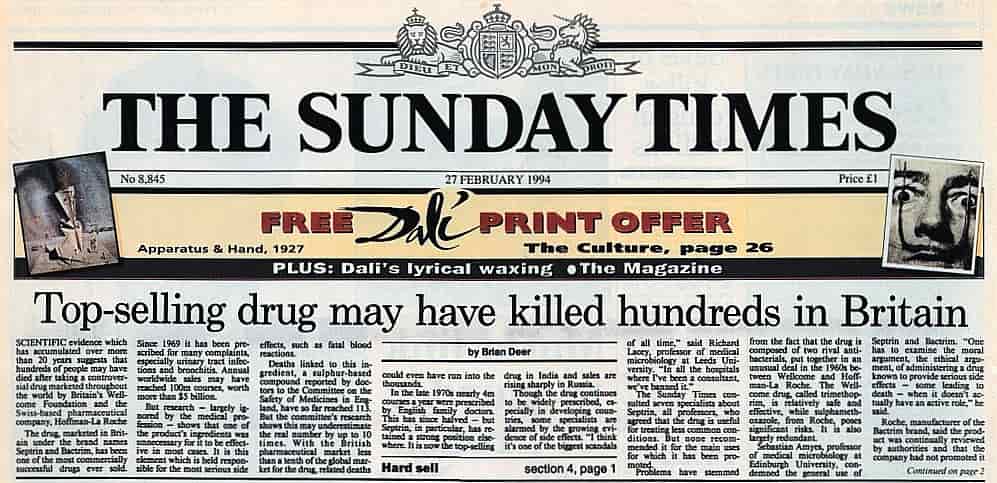

Top-selling drug may have killed hundreds in Britain

The Sunday Times

February 27 1994

By Brian Deer

Scientific evidence which has accumulated over more than 20 years suggests that hundreds of people may have died after taking a controversial drug marketed throughout the world by Britain’s Wellcome Foundation and the Swiss-based pharmaceutical company Hoffman-La Roche.

The drug, marketed in Britain under the brand names Septrin and Bactrim, has been one of the most commercially successful drugs ever. Since 1969 it has been prescribed for many complaints, especially urinary tract infections and bronchitis. Annual world-wide sales may have reached 100m courses, worth more than $5 billion.

Follow Brian on Twitter:

But research – largely ignored by the medical profession – shows that one of the product’s ingredients was unnecessary for it to be effective in most cases. It is this element which is held responsible for the most serious side-effects, such as fatal blood reactions.

Deaths linked to this ingredient, a sulphur-based compound, reported to the Committee on the Safety of Medicines in England, have so far reached 113. But the committee’s research shows this may underestimate the real number by up to 10 times. With the British pharmaceutical market less than a tenth of the global market for the drug, related deaths could have run into the thousands.

In the late 1970s nearly 4m courses a year were prescribed by English family doctors. This has since halved – but Septrin has retained a strong position elsewhere. It is now the top-selling drug in India and sales are rising sharply in Russia.

Though the drug continues to be widely prescribed, especially in developing countries, some specialists are alarmed by the growing evidence of side-effects. “I think it’s one of the biggest scandals of all time,” said Richard Lacey, professor of medical microbiology at Leeds University. “In all the hospitals where I’ve been a consultant, we’ve banned it.”

The Sunday Times consulted seven specialists about Septrin, all professors, who agreed that the drug is useful for treating less common conditions. But none recommended it for the main uses for which it has been promoted.

Problems have stemmed from the fact that the drug is composed of two rival antibacterials put together in an unusual deal in the 1960s between Wellcome and Hoffman-La Roche. The Wellcome drug, called trimethoprim, is relatively safe and effective, while sulphamethoxazole, from Roche, poses significant risks and is largely redundant.

Sebastian Amyes, professor of medical microbiology at Edinburgh University, condemned the general use of Septrin and Bactrim. “One has to examine the moral argument, the ethical argument, of administering a drug known to provoke serious side-effects – some leading to death – when it doesn’t have an active role,” he said.

Roche, manufacturer of the Bactrim brand, said the product was continually reviewed by authorities and that the company had not promoted it for years. “Serious and occasionally fatal reactions have been associated with the product,” it said, “but these are rare.”

Disclosures about Septrin come at an awkward time for Wellcome, which is facing doubts about its Aids drug AZT. The company was also forced to pay £2.75m last year after a ruling in the Irish courts that its whooping cough vaccine caused brain damage. Wellcome said millions had benefited from Septrin, that it was better for treating drug-resistant strains of bacteria, and disputed the claim that associated deaths were unnecessarily high. Neither Septrin nor Bactrim has been compulsorily withdrawn from any market world-wide.

The drug sprang from the success of a Nobel prize-winning Wellcome scientist, Dr George Hitchings, who patented trimethoprim in 1957. From the outset it was clear that it could be a powerful rival to the traditional penicillin antibiotics and to older sulphur-based compounds, or sulphonamides.

Roche was the biggest sulphonamide manufacturer and saw the implications of a newer and safer alternative. Wellcome was still a small pharmaceutical house with little industrial muscle. Rather than launch trimethoprim, executives realised that the best way to proceed was to go into partnership with Roche. So the two drugs were combined in a large, multipurpose pill.

Commercially, the advantages were clear. Together they could effectively promote to doctors the idea of switching from penicillins to the new combination product. But soon after the combined pill was marketed, evidence began to accumulate that there was rarely any justification in taking two antibacterials rather than one.

A paper in the British Medical Journal in 1972 reported an identical cure rate with Hitchings’s compound as there was with the combination. Moreover, it noted, “trimethoprim alone was remarkable in causing fewer than half the side-effects.” Many more reports followed over the next decade.

Follow Brian on Twitter:

But despite these reports, which were not challenged, Wellcome, in particular, stepped-up its promotion. From 1981, for instance, it had a full-colour advertisement for Septrin in every issue of the journal World Medicine for a year.

Dr Joe Collier, editor of the Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin, believes this heavy promotion explains why the product is still widely prescribed. “The drug companies have enormous power to produce their advertisements, which they can hammer on home, bang, bang,” he said.

>>> The drug company Wellcome threatens >>>

RELATED:

Bactrim – Septra: a secret epidemic

Chronology of a newspaper campaign

The many faces of Bactrim and Septra

>>> Go to emails to this website >>>

SYMPTOM SEARCHER: This site has hundreds of visitors’ experiences. Enter Bactrim and your keywords in the SEARCH BOX on any page