>>> More social affairs >>>

Reprint

![]()

Social whirl sets reporting trends

UK Press Gazette, May 30 1988

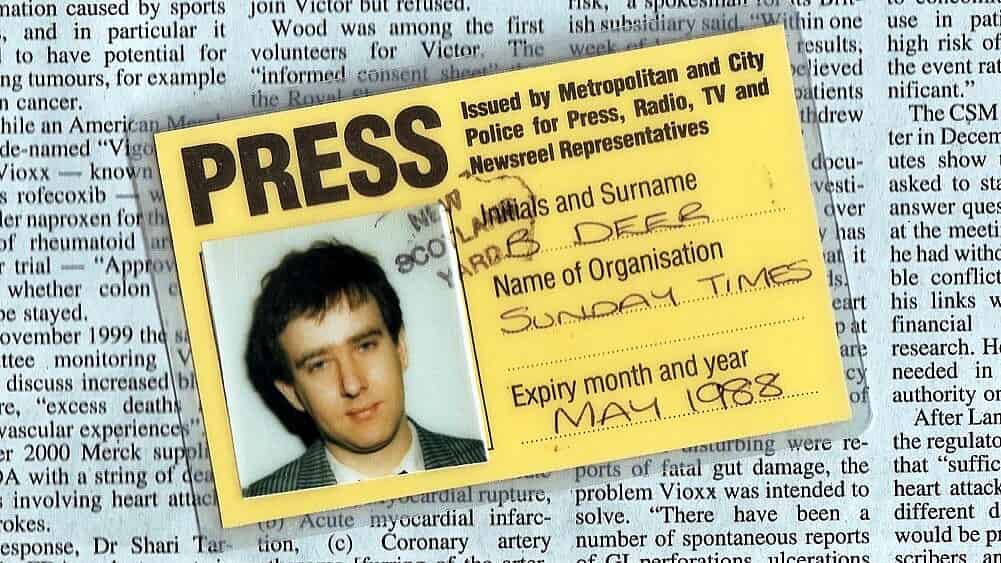

By Brian Deer

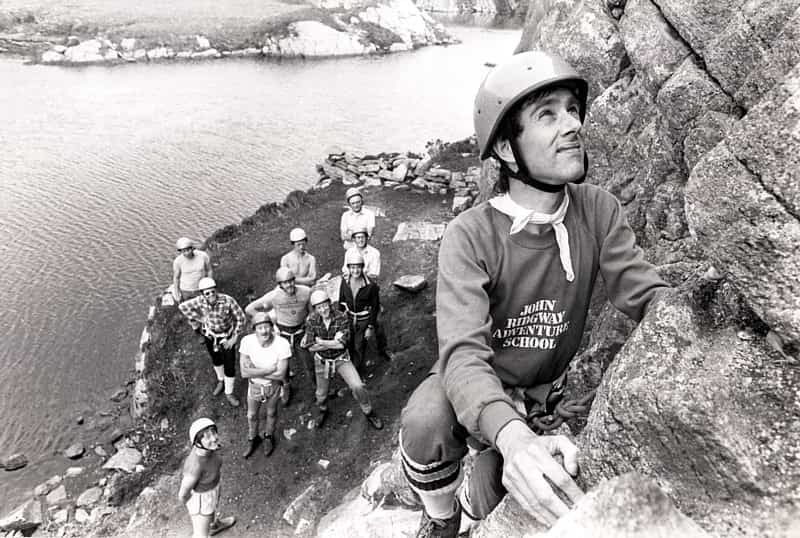

Social affairs is currently the boom area of serious journalism, says Brian Deer [picture], who is in charge of the beat for The Sunday Times. It is also a very challenging specialism requiring a soft heart, a hard nose, a quick brain and a good capacity for striking a balance.

If you feel that social affairs are things that begin at dinner parties and invariably end in tears, the time has arrived when you’ll have to think again. Social affairs is now the fastest-growing beat in journalism and is set to become a powerful force in news and current affairs.

Sunday Times editor Andrew Neil was first off the mark, giving a reporter (as it happens, myself) the title of social affairs correspondent two and a half years ago. The Western Mail followed soon after, and more recently the Press Association and the Financial Times have both created the job.

But the biggest boost lately has come from the BBC, where John Birt, the deputy director general, announced last month that he was creating a whole social affairs group for television and radio as part of his overhaul of broadcast journalism.

The arrival of these new jobs should not be a surprise. We are now in the period of what The Times last October called “the social affairs parliament” In health, social security, housing, crime prevention, local government and education, the government has embarked on a revolution that must be reported well.

No end of social issues are coming to the fore. The position of pensioners in an ageing population, the role of custody with prisons overcrowded, the rise in awareness of how we abuse the young, the multiple deprivations in the inner cities, the life-opportunities open to the poor and unemployed.

In the past, some aspects of the work have been carried out by social services correspondents. But, like labour editors, who are dying out as trade unions lose their political clout, the social services staffs are in terminal decline as the landscape is transformed by social change.

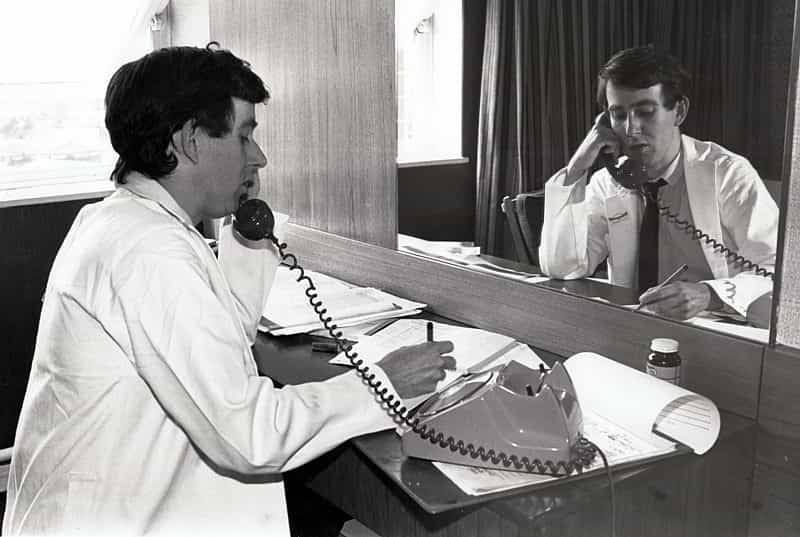

For the national dailies, the most practical result is the growth of concern about health care. Covering the NHS is now a big enough job alone for any correspondent, and there has never been any logical reason why social security, another booming field of reporting, should be bolted onto it.

In other countries, social affairs has long been an established concept. Many governments have a cabinet minister for the area, often combined with responsibility for employment, and Mrs Thatcher is at present considering breaking up health and social security and creating such a department here.

But for Sunday papers and broadcasters in particular, social affairs journalism has been born out of a recognition that for one member of the staff, or a team, to consider the various social issues together produces an understanding of the whole that is greater than the sum of the parts.

My paper’s “Old and Cold” campaign for the elderly in winter, for example, needed to move quickly with a detailed understanding of social security, housing and social services provisions, as well as the networks needed to produce real instances of people in difficulty who were willing to be photographed.

Take, again, the position of children in care. Their welfare will be considered by a local authority case conference which may include a doctor, a social worker, a teacher, a health visitor, a probation officer, the police, and sometimes other specialists.

A good social affairs journalist would know the professional networks, problems and language of any of these people – gaining the chance to avoid ignorant or naive reporting, and perhaps counter the frequently misleading steers on policy from government “sources”.

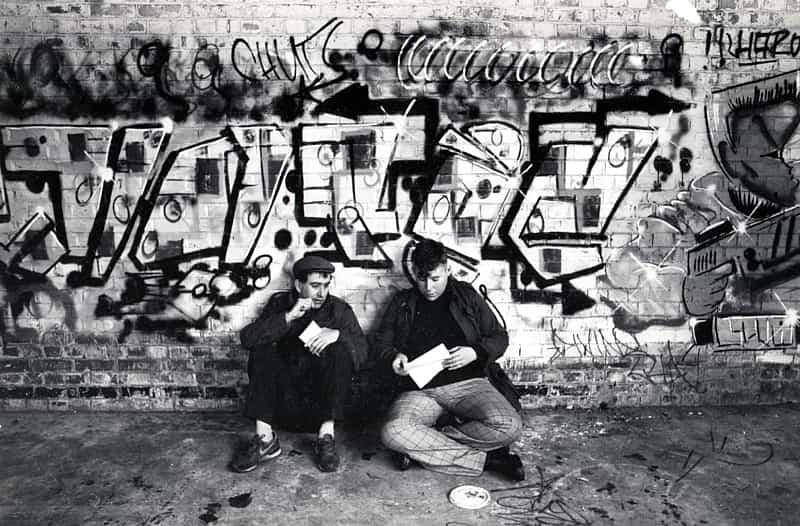

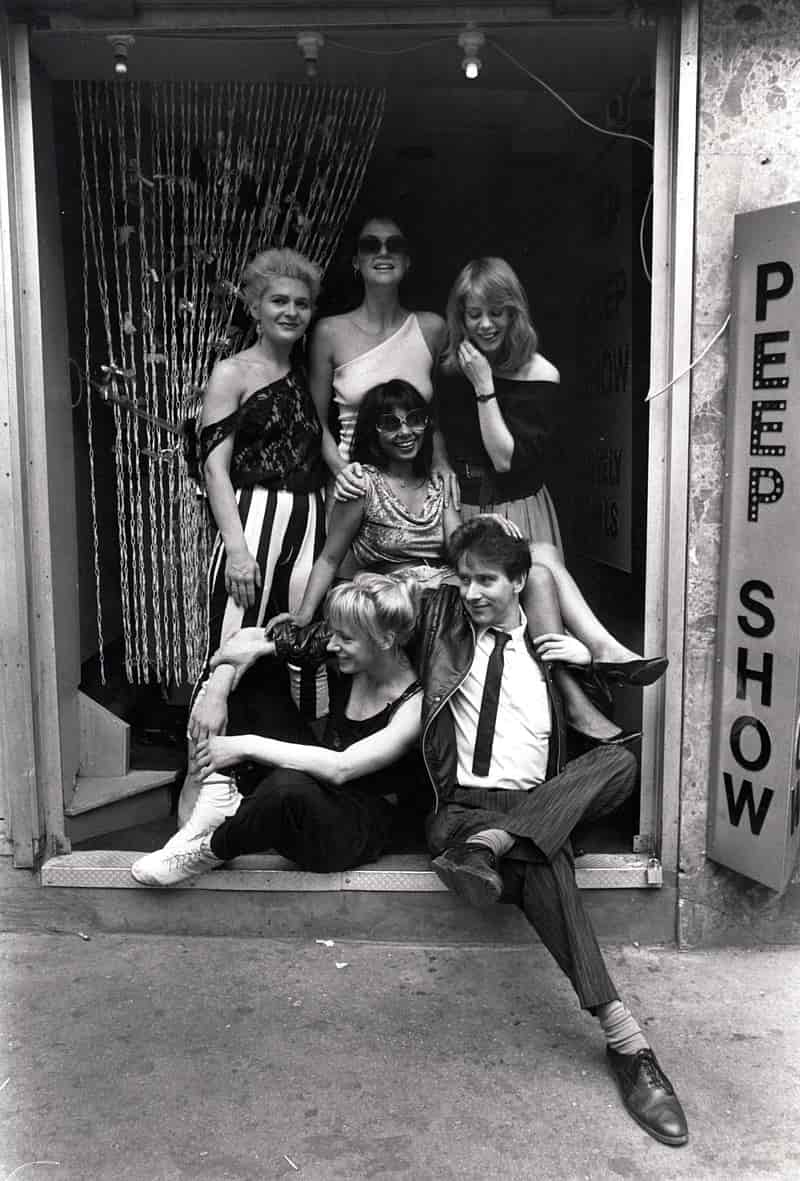

Even more important, however, is the need for this new specialism to go direct to primary sources. Good reporting means talking to junkies about heroin, to children about the Cleveland scandal, and to claimants about benefit changes – efforts that are not made by political staffs and which are sometimes used unprofitably by general reporters.

Since the reality in the social front-line often clashes with the voice of government, the social affairs specialist has a tough political task to balance out conflicting views of the world. Too tough-minded and nobody will speak to you. Too heartfelt in your treatment and nothing much is useable.

Social affairs is also very much about an attitude of mind. At The Sunday Times, we like to think that there is as much dignity in the words of a bag lady as in those of a full-blown secretary of state – and both are often surprised, and sometimes pleased, to be treated as equals when it comes to an interview.

Spending a lot of time with the 25% or so of the population who are missing out on the material gains of the Thatcher years is bound to rub off on even the most hard-bitten reporter. And like the old social services people, the social affairs correspondent is bound to be seen as a liberal.

Doubtless this will add to our reputation in some quarters as the moaning minnies’ staff, but as the government ploughs on with welfare, health, housing, education and local government finance reform, social affairs journalism is very much a specialism whose time has arrived.

>>> Take the social affairs tour >>>

Topic: Social affairs: defining a speciality

>>> More social affairs >>>

RELATED:

Thatcher: No such thing as society

Brian Deer: reporting the 1980s