Reprint

![]()

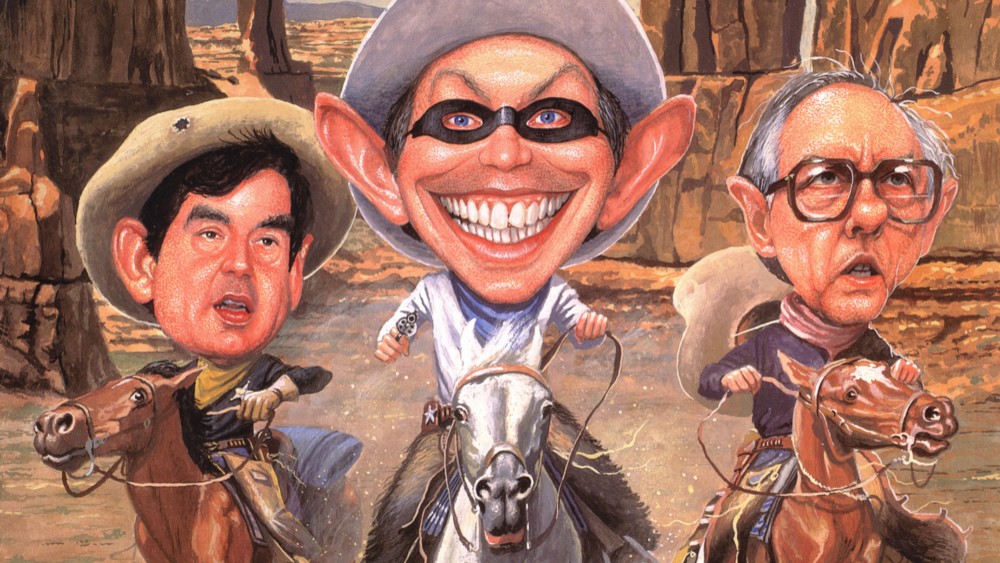

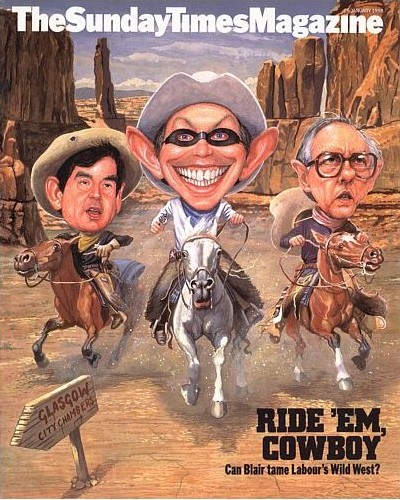

Hang ’em high

It is high noon for old Labour. Tony Blair has sent a posse to drive out its die-hard socialists, and this week the fate of leading party members is to be decided. But is new Labour just looking for a lynching?

The Sunday Times Magazine

January 25 1998

INVESTIGATION by BRIAN DEER

A year ago next week, Bob Gould, who was then leader of the Glasgow City Council, gathered up his agenda and minutes, kicked back his chair and stormed out of a heated meeting of the local authority’s Labour group. He was 61 years old, with a shock of white hair. His normal manner was subdued and easygoing. He possessed a style polished over 26 years as a Scottish political fixer. But as he slammed the door of the committee room behind him, he momentarily lost his cool. “I resign,” he blazed to friends in hot pursuit. “I’m not taking any more of this crap.”

It was the kind of emotional flare-up you might easily witness in any town hall in Britain. Gould’s ruling caucus of Labour councillors had been debating an £80m package of spending cuts, and his own proposals had just been thrown out by 64 votes to 3. After retiring to his office, on the second floor of Glasgow’s magnificent City Chambers building, he recovered his demeanour and announced to reporters that he hadn’t quit after all. And the following day he explained more calmly that he had merely been feeling frustrated. To win his colleagues’ support, he added offhandedly, it helped to promise them foreign trips.

Bang, bang. The ricochet resounded, to the delight of opposition parties. In the fraught run-up to the May general election, the casual hint of bribery in the region was a bloodying bullet in Labour’s foot. On February 5, under the headline “Give us a trip and we’ll vote for you,” the Evening Times, Glasgow, led a frenzied media alarm over the party’s ethics with a devastating quote from Gould. “Surely someone wouldn’t back you simply because you agreed to send them on a trip for a couple of days,” he said. “But that’s what we’re faced with.”

Bang, bang. The ricochet resounded, to the delight of opposition parties. In the fraught run-up to the May general election, the casual hint of bribery in the region was a bloodying bullet in Labour’s foot. On February 5, under the headline “Give us a trip and we’ll vote for you,” the Evening Times, Glasgow, led a frenzied media alarm over the party’s ethics with a devastating quote from Gould. “Surely someone wouldn’t back you simply because you agreed to send them on a trip for a couple of days,” he said. “But that’s what we’re faced with.”

On its own, the outrage that followed this assertion might quickly have run its course. The Labour Party has controlled Glasgow almost uninterrupted since 1933, and the city’s people have long got used to strange stories about local politicians. Much as boxing was once a route out of poverty in London’s East End, in the west of Scotland politics has commonly been a road to a better way of life than mere work. When it later came out, for instance, that the chairman of the parks and recreation committee had travelled to Hong Kong at their expense, and that the housing chairman had spent ten days in Istanbul, nobody was in the least bit fazed.

But Gould’s “votes-for-junkets” revelation followed two other Labour scandals on Clydeside, and was about to be joined by two more. By the end of the summer, party managers were dealing with an astonishing accumulation of allegations in and around Glasgow, including religious sectarianism, nepotism, links to drug dealing and organised crime, ballot-rigging, bribing a rival parliamentary candidate, and whispering campaigns that preceded the suicide of the MP for Paisley South. Never in recent history have so many claims of “sleaze” stacked up in one geographic location.

At first sight they seemed like a potential embarrassment to the Labour Party’s image as a whole. After John Major’s Conservative government left office dogged by allegations of “sleaze”, Blair’s administration has been struggling to appear as being above the fray of impropriety. But as the months have passed, some observers have wondered whether the scandals that Gould flagged might not be viewed in Downing Street as an opportunity to accomplish other goals. If anywhere could be described as the wild frontier of “old Labour” socialism, it is here towards the western end of Scotland’s urbanised central belt. And just as Neil Kinnock, the former Labour leader, stamped his authority on the party in the 1980s by confronting Militant Tendency socialists in Liverpool, so they say that Blair may feel that a showdown on Clydeside could help his longterm project.

*****

The scandal which set the template for the furore sparked by Gould occurred in Monklands District Council, a now-abolished authority, on Glasgow’s eastern fringe. In June 1994, a parliamentary by-election caused by the death of the Labour leader, John Smith, became embroiled in claims that the mostly-Catholic council leaders favoured spending in areas where their religion predominated and shunned those which were largely Protestant. An independent inquiry, one year later, also found that the local authority employed almost 70 relatives of councillors.

Meanwhile, by Glasgow airport, to the city’s west, another bomb went off. In November 1995, the party’s national executive in London stepped in to block the deselection of Irene Adams, aged 50, the MP for Paisley North, after she had alleged that her local constituency organisation had been infiltrated by drug dealers and gangsters. She claimed that a community body on a housing estate, involving councillors, was a “front” for corruption, and that scores of bogus membership applications had been submitted by her opponents.

Both the Monklands and Paisley rows were simmering unresolved when Gould made his votes-for-trips claim. And then – even as party officials probed the Glasgow leader’s allegations – two more scandals burst into the open, involving Clydeside members of parliament. First, the general election poll in the Govan constituency, on the river’s south bank, was allegedly rigged with non-existent “ghost electors”, with the victorious Labour nominee, cash-and-carry millionaire Mohammed Sarwar, 46, admitting handing £5,000 (which he said was a loan) to a rival Asian candidate. Then in June, after the MP for Paisley South, Gordon McMaster, killed himself in his garage, the neighbouring member, West Renfrewshire’s Tommy Graham, 53, was accused of running a “smear campaign” that drove his Commons colleague to his death.

No surprise: Labour’s high command has been swift and decisive in response. Under the supervision of Donald Dewar, now Scottish Secretary and expected to become a devolved Scotland’s first minister next year, the reaction from London was heavy. In Monklands, the entire ruling group of 15 councillors was suspended and barred for two years from holding party office. In Paisley, constituency bodies were shut down, two councillors linked with the community body suspended and numerous activists had their membership renewals “deferred”. Finally, last summer, the parliamentary whip was withdrawn from Sarwar and Graham.

In the run up to the general election on May 1 and the devolution poll on September 11, this take-no-prisoners show of strength from London was at first interpreted as straightforward damage-limitation. With so many bizarre goings-on in the same place at the same time, there was a risk of a public perception emerging that Tony Blair’s Labour was no freer from sleaze than John Major’s Conservatives were.

But there were also signs of another agenda – and of a political opportunity for Blair. Clydeside is not only a Labour stronghold, it is also more than anywhere else in Britain the heartland of its traditional philosophy. Rooted in heavy industry and trade unionism, and with the birthplace of the party’s first MP, Keir Hardie, just down the road in Lanarkshire, here is the United Kingdom’s greatest socialist fortress, more important even than Liverpool or inner London. And just as Neil Kinnock, the former party leader, promoted a tough-guy image with the public through his duel with Militant Tendency in Liverpool during the 1980s, so Blair appears determined to enhance his authority by tackling old Labour in the west of Scotland.

With such ambitious game plans in mind behind the scenes, the votes-for-trips inquiry sparked by Gould’s remarks, was upgraded to a wider review. At the City Chambers, a six-month investigation took place during which 37 councillors were grilled by officials, and on September 24 it was announced that at least five city leaders and four backbenchers would be suspended and possibly expelled. Their fate is to be determined at the end of this week by the party’s four-person national constitutional committee, set up in 1988 for Kinnock’s purposes.

Of these nine, the most high-profile on the Clydeside landscape is Pat Lally, the 71-year-old lord provost of Glasgow – a ceremonial post equivalent to an English lord mayor. Also on the list was his deputy provost, Alex Mosson, plus Gould’s deputy leader, Gordon McDairmid, and the head of parks and recreation, James Mutter.

But there was also a suspension that surprised everybody: the apparent whistleblowing leader, Gould himself. On the September morning when disciplinary action was announced to the media, he was telephoned at his office by the party’s Scottish head office, warning that in the afternoon the national executive in London would take action against him too. “It was a total shock,” said one of his supporters, a councillor, who asked not to be named. “He was trying to sort out the mess at the City Chambers and he found himself out on his ear.”

Taken at face value, it seemed a strange reward – and there was another peculiarity in the affair. After briefly examining the votes-for-trips allegations, officials, led by Jack McConnell, the party’s Scottish general secretary, and Eileen Murfin, a national officer from London, embarked on a fishing expedition in an apparent bid to solicit more criticisms of the accused. And in a string of Scottish media exclusives, the public were regaled with stories in which councillors accused each other of a bizarre rag-bag of offences, from violence and threatening behaviour, to spreading malicious smears about opponents’ sex lives, to non-payment of rent and of failing to operate within “accepted procedures”. Gould was charged with poor leadership of the city’s Labour group and was forced to stand down from his job.

With so many allegations being bandied around, officials said they were anxious for caution. “If anybody is found guilty of misconduct,” McConnell declared, after presenting a report in October to the national executive, “the action will be firm and strong.”

But with growing signs of tension throughout the UK between Blairites and traditional socialists in the party, many observers believe that the crackdown on Clydeside is motivated as much by a desire to assert control as by an interest in curbing any abuses. In short, that new Labour has embarked on rough justice, determined to destroy its foes.

*****

The Glasgow City Chambers building was constructed as a sumptuous citadel of power – power in which the people were not meant to share. It was completed in 1889, at the very peak of the British Empire, when a mighty congregation of capital and labour allowed the city’s fathers to boast that they presided over “the industrial workshop of the world”. The building was essentially a club for landlords, merchants and proprietors, who for the most part entered politics because it let them rub shoulders with the aristocracy and idle rich. In this, the most spectacular of Britain’s municipal headquarters, a culture of remote paternalism was forged as durable as its 10m bricks.

The building commands the east side of George Square and was designed in the style of an Italian palace, with grandiose pinnacles and balustrades. Inside there are marble staircases, mosaic floors and glazed pottery walls and ceilings of such exquisite extravagance that by comparison Westminster is a railway station. There are great glass domes and chandeliers, rich carpets and finely-carved woodwork. The council leader and the lord provost enjoy offices that, fittingly, resemble the sanctuaries of Borgia princes.

The grandest spaces are most often deserted, like an upper class Victorian villa. But every six weeks a sporadic bell-clanging suggests some frenetic activity within. This is a signal that a council session is in progress and that a division is taking place. Red-collared flunkies throw open heavy doors, and members who have wandered off to attend to other matters scurry in to cast their votes. The chief executive rises, surveys a semicircle of mahogany pews (where typically around 80 councillors sit under the enthroned lord provost’s gaze) and declares the motion to be “carried by a large majority”.

But here is a snag for the people they represent: all the bell-clanging and vote-casting is a farce. Such is Labour’s stranglehold on the city that of the 83 members returned in the last elections – 1995 – 77 were from the ruling party. A paltry three were Conservatives, while the Scottish National Party, Liberal Democrats and Militant Labour all struggled to win one each. So, there may be the appearance of some kind of democracy in action, but the sessions are merely rubber-stamping in public what has been decided in private by Labour. The chief executive makes the same large majority declaration whatever the business in hand.

There are, moreover, no real differences of philosophy among members of the ruling group. At last month’s meeting, when a nationalist motion was proposed attacking the government’s education policies and, particularly, the introduction of tuition fees, the majority mostly gossiped throughout the proceedings, read newspapers or shuffled in their pews. A noncommittal “delete all and insert” amendment was then mechanically carried, squashing the criticisms like a fly on the windscreen with, as ever, “a large majority”.

Their Victorian forebears would have been no more laid-back, and not surprisingly, the opposition is miffed. “The Labour local election manifesto indicated that they would have open, democratic government,” John Young, leader of the tiny Conservative group told me. “Now, I have been a councillor here for 33 years and this is the least open and the least democratic government that I have ever seen. All of the major decisions take place behind closed doors. If you’re talking about school closures, or things like that, no parents, no teachers, no children ever hear what sort of arguments are put up, one way or another.”

The council chamber is the dreariest theatre. All the action takes place backstage. As Gould demonstrated when he stormed from the Labour group, an internecine battle rages behind the common philosophy as vicious as in any town hall. Without any need to win arguments with political opponents, the ruling party has split into warring factions, whose clashes dominate council affairs. “Verbal evidence,” officials have reported to their national executive, “was consistent in describing an almost total absence of good working relationships within the Labour group and of fierce factionalism which has become accepted as part of the normal situation.”

Gould presently leads of one of these fierce factions, which is about two dozen councillors strong. Like most of his colleagues who assemble in the chamber, he flaunts the kind of working class credentials which are still a boon to Scottish politicians. Having grown up in the Springburn neighbourhood of the city, he became a railwayman and then a trade union official. Before joining the city council, rose to lead the now-abolished Strathclyde regional authority, whose drab, functional administrative offices were less than a mile from the sumptuous City Chambers.

The other faction, perhaps half as big again, is led by Lally, the ageing lord provost. He, too, has impressive origins, having grown up in a single room and kitchen in the legendary (and long-demolished) Gorbals slums. He once worked in a drapers, but in 1967 was elected to what was then the Glasgow Corporation. His admirers regard him as the grand old man of West of Scotland politics, and after clearing himself of wrongdoing following a bribes-for-housing scandal in the 1970s, he has earnt himself the nickname “Lazarus”.

Gould sees himself as an old-style right-winger, while Lally’s supporters call themselves “Tribunites”. But what came into the open with the votes-for-trips outburst was not a division rooted in ideology. Both men are traditional tax-and-spend socialists, with no love for prime minister Blair. When the council leader stormed from the group after being defeated over the cuts package, it was not because he, or anyone else of any consequence, suggested they shouldn’t go ahead. The point at issue was merely the question of whether the authority’s employees should forgo a 2.5% wage rise to avoid redundancy.

Mere matters of politics are the small beer of dispute here. Tribalism, pure and simple, drives conflict. Gould and 17 councillors used to serve on the giant Strathclyde regional authority, once Europe’s biggest local government body. Another 37, meanwhile used to sit with Lally as Glasgow district councillors. On April Fools Day 1996, the region and district were fused in a new entity – the Glasgow City Council – and, straightaway, a feud broke out. Cut to its core, Scotland’s biggest city’s politics is shaped less by uncertainties on the socialist road than by crude personal rivalries and hatred.

*****

Labour’s internal feud at Glasgow City Council sounds like one of those one-off situation, too embedded in personalities to be untangled. But, however the situations appear to superficially shape-shift, a similar story holds constant across Clydeside. Not only is Labour’s dominance absolute throughout the region (the party won all of Glasgow’s 10 parliamentary seats last May with majorities averaging 13,000 and made a clean sweep of the dozen in the surrounding conurbation) but everywhere you look you see the same tribal faction fights and parallels in the sleaze allegations.

In the old weaving town of Paisley, the claims of corruption were laid only after a quarrel developed between Tommy Graham MP, a former Rolls-Royce fitter, and the late Gordon McMaster MP, previously a gardener. In Monklands, accusations surfaced after hostilities broke out between councillors in the towns of Airdrie and Coatbridge. And in Govan, the Sarwar “electoral fraud” disaster was born out of a squabble for the party’s nomination, when improprieties on all sides were alleged. And while these conflicts have superficial elements of, respectively, old-new Labour, Catholic-Protestant and Asian-white, these features obscure the common denominator: the bitter enmity of rival cliques.

Some people have wondered if there isn’t something in the water supply to explain the geographic concentration. But those who have tried to probe below the surface point to wider forces at work. “There is a vacuum at the base of the Labour Party,” John Foster, professor of applied social studies at Paisley University, said. “We have not only seen an end to any effective opposition in Scotland, but we’ve seen a withering away of powerful organisations, such as trade unions, tenants associations and community groups, that were once a check on politicians.”

As such sticks of opposition have been broken, moreover, carrots have been on hand to incite personal jealousies for the spoils of political power. With Labour candidates near-certain to win elections, insidious networks have grown up within the party to share the more immediate rewards. In an area where jobs are scarce and skills often redundant, for instance, councillors get £6,000 basic pay (which for some is all they live on), plus £18,000 if they hold a committee chair – which around half of them do at any time. For many, the alternative to holding public office would be retirement or life on the dole.

Not surprisingly, incumbents have sometimes not wanted to expose their positions to challenge. Countless stories go round of party branches where membership lists have been said to be “closed” to new applications, while meetings are regularly inquorate. There have long been an unusually large number of husband-and-wife teams holding council and parliamentary seats. And union affiliations mysteriously rise and fall, corresponding to the various posts up for grabs. Dominant individuals, such as Gould and Lally, are mirrored in bare-knuckles everywhere.

In the face of the potential for naked cronyism, traditional disadvantages, such as lack of education, poor social skills and even low intelligence have not been regarded as critical obstacles to acquiring public office. For all the idealism stretching back to the legendary Hardie, because the party has also offered the chance of advancement, it is has also provoked the Clydeside equivalent to the Blairites’ middle class opportunism.

“There’s a story that people tell here about someone who wanted to be a candidate, and he was asked to outline his convictions,” a former member of the party’s Scottish executive joked with me. “He thought they meant his criminal record and asked how far back they wanted him to go.”

*****

The people of Clydeside are rightly known for their toughness. Two hundred years of the economy explains it. The workshop of the world was racked by boom and slump to a degree barely known elsewhere. When the order books filled, at the shipyards especially, even those families in the most overcrowded slums would celebrate comparative good fortune. But when business turned down, as in time it always did, their plight was incomparably cruel. The stereotyped view is that this cycle encouraged drinking, but it also bred a resilience in the face of adversity that became part of the region’s soul.

The economy which rollercoastered in the Council Chambers’ golden days produced strident class-based politics. In the face of appalling deprivation during slumps, the unions achieved an unparalleled bargaining power when the labour market tightened during booms. And though today the great shipyards, steelworks, mills and factories which once dominated Clydeside are long gone (with not even a book of memories in the Sauchiehall Street Waterstones) there are few who doubt that the footprints of heavy industry are left deeply embedded in the landscape.

“There is a continuing inheritance that comes through right from the early 1900s,” Ian Donnachie, senior lecturer in history at the Open University and editor of Forward!, a textbook on Scottish Labour politics, said. “It’s the tradition of the skilled working class employed in large enterprises, and this is what has really driven the socialist movement forward in this country.”

Heavy industry and highly-regimented, factory-based jobs were the foundations of both trade unionism and socialism. But just as they were more powerfully forged in this part of Britain than anywhere else, so a chink in the armour of the Labour programme was found here before anywhere else needed to look. One reason for sustained capital investment on Clydeside was that, for all the formidable organisation of the workforce, it remained timelessly divided against itself. Feuds expressed in terms of religion, in particular, but also of nationality, shades of social class, Scottish regional origin, trade sector and level of skill, provided what many have noted as a fatal brittleness in the region’s hard facade. For all its reputation as the foundry of the Left, the history of “Red Clyde” militancy included any number of self-inflicted wounds.

As the region today is reborn from a quarter century of industrial collapse and restructuring, some think that the new Labour leadership in London is emulating the strategy of the old bosses. They argue, in short, that (with varying motivations) Blair, Donald Dewar and Gordon Brown, the powerful chancellor and Scot, want to play the game of divide and rule. “New Labour?” Alex Mosson, Lally’s deputy and a former shipyard worker, said in a newspaper interview last year, before being banned by party officials from any further comment. “There is nothing new about new Labour. It is only new capitalism dressed up.”

Mosson’s argument is familiar, but there is some evidence that it’s not a Clyde’s width far from relevant. Until party managers were jolted by Sarwar’s appearance in court on December 17 to deny charges of electoral fraud, they appeared to do nothing to discourage the public sense that something was wrong in their ranks. If anything, officials appeared to stoke more rancour in the heartland of their Scottish support. Internal information has been leaked to the press; decisions of the national executive revealed before the executive has even sat down; and rumour-spawning investigations have been left to drag on until a full year has now elapsed.

It also seems clear that Blair has predetermined that the suspended councillors should be axed. Although the party’s constitutional committee doesn’t even meet to consider the allegations until this Friday, it was leaked three weeks ago that Lally – a party member for 47 years – is to be expelled for life, Mosson is to be suspended for five years and three others are to be suspended for three years. Gould is “expected” to be allowed to remain, although his case is said to be viewed “seriously”.

But, even with the stoking, the delays and the prejudgment, the basis for the charges of sleaze at the City Chambers have, oddly, shrunk to nothing over the year. Council records show that, despite Gould’s outburst, all foreign trips had been properly approved, and that compared with overseas excursions by members of parliament, any “junkets” were hardly excessive. In the ten months before the row, a total of 12 councillors had been on a total of 19 foreign trips to 15 different destinations. Most, however, involved the lord provost, who spent 36 days in the Far East, 15 in North America and seven in Europe, promoting the city in his ceremonial capacity – in other words, doing his job.

The accuser, Gould, meanwhile, had spent 11 days abroad, making his allegations of apparent junketing by other councillors seem wrong, if not downright a reckless. And on October 28, opposition councillors, from all parties – Conservative to Militant – rallied to exonerate the suspended members, proposing a motion that the beleaguered Labour leaders should keep their prized chairmanships of committees.

With the junkets allegation missing its mark, party officials then came up with more intangible charges of misconduct. In a secret internal report leaked from Keir Hardie House, Gould was said to have “failed to offer appropriate leadership to the group” – shock, horror – while his deputy, McDairmid was alleged to have “sought to undermine the group leadership.”

Lally meanwhile was accused of having “failed to maintain the standards required of a public representative of the party”, but there was no real hint of what that was. The only substantive criticism of the lord provost was contained in a 100-page letter sent to the defendants during Christmas week in which he was said to have authorised the use of too many cars in a trip to the Edinburgh Tattoo. Nineteen councillors, officers and business leaders took four vehicles (including a stretch limo) to champion Glasgow at the rival city’s big event, at a cost of £450, including a dinner, drivers’ overtime and parking.

There are no allegations of criminality against either man. No investigation has been launched by the Glasgow district auditor. And barely a person in the City Chambers would argue that any misconduct was more than stupidity. But, after a two-day hearing this week, the constitutional committee is expected to issue a statement next month that evidence of misconduct has been proved. “It’s no more than a formality,” said one senior city council employee. “This is scary stuff.”

*****

Whatever the strengths and weakness of the charges, every sign points to the covert execution of Blair’s new Labour agenda. For all the squabbling between Gould and Lally, the City Chambers sits not only in the socialist heartlands, but some say is potentially the citadel of power for the most potent town hall movement in Britain. Sources, ranging from the Conservative opposition to council staff, say the concealed issue is not really misconduct in Scotland, but a desire in London to take control.

“Labour’s official investigators made their trip north on a quite specific mission,” argued Bill Robertson, a local newspaper journalist who has sat through meetings at the Council Chambers for 15 years. “It was to create sufficient casualties to destabilise the ruling clique and demolish the biggest power base of old Labour in Scotland. With Glasgow sorted out, the hearts and minds of party activists elsewhere will quickly fall into line.”

It’s a cynically bleak scenario, but the apparent weakness of the disciplinary charges again finds parallel on Clydeside. In Monklands, a second inquiry into the religious sectarianism issue reached an inconclusive result. In Paisley, no evidence of criminal activity or infiltration has been found. The MP Graham was quickly cleared of any role in McMaster’s suicide. And, just as with the purge of Militant in the 1980s, inquiries have more and more focused on hearsay, rumour and suspected “associations”.

Meanwhile, the public spotlight on the issues is encouraged – devastating the accused, guilty or not. Suspension has cost senior councillors their “special responsibility” allowances, which are sometimes their families’ only incomes. Glasgow’s former deputy leader, McDairmid, has been gone sick from work and has cancelled surgeries because, friends say, he’s ill. Joan Graham, the MP’s wife, has had a heart attack. And many of the accused say that neighbours now revile them because of how the word “sleaze” sticks.

To date, there has been reluctance to defend the individuals, but this may be starting to change. “As somebody who is identified with old Labour in terms of policy attitudes, I strongly resent efforts to attach indefensible behaviour to long-standing members of the party,” said Maria Fyfe, MP for Glasgow, Maryhill, who was one of 47 who voted against the government in last month’s row over lone parent benefits. “They should at least get on with their inquiries and form conclusions one way or the other.”

Whether more of old Labour – particularly in England – will rally to the councillors’ aid now appears to depend on how the constitutional committee fulfils its brief this week. It’s unlikely to snub Blair, but there are growing signs that it may provoke a backlash if it strike’s unfairly at the party’s traditionalists. The defeat last autumn of Peter Mandelson by Ken Livingstone for a place on the national executive (in a postal ballot dominated by new members), as well as the anger over the government’s scrapping of free higher education, and the benefits revolt, are all signs that abruptly dumping the party’s heritage goes against the membership’s grain.

Dewar, the Scottish Secretary, has been encouraged that, so far, the apparent scandals have edged the party further down the modernising road. Evidence from selection meetings suggests that the disgrace of councillors and MPs is benefiting the same kind of educated, middle class Blairites who have seized key positions elsewhere. A pro-leadership group called the Network has scored impressive victories on the party’s Scottish executive and in selections for parliamentary seats. And after McMaster’s suicide, Brown, the chancellor, effortlessly parachuted one of his protégés into Paisley South: the 30-year-old solicitor, Douglas Alexander.

But despite these successes, the Blairite strategy is fraught with political risk. Much of Labour’s Scottish bedrock is what is some call the “numpty vote” – people who back it for vague historical reasons, or out of tribal class hatred for Tories. With old Labour tainted by sleaze allegations and new Labour increasingly seen as the heirs to Thatcherism, many observers expect the party’s Scottish ascendancy may slip further in the direction of the nationalists.

“Suspending individuals is one thing, but proving that the underlying problems that led to the suspensions have been dealt with is another matter,” Michael Russell, the Scottish National Party’s chief executive argued. “They are in a cleft stick now. There is a public perception of corruption in old Labour’s one-party state, and no sense that there is anything reassuring about new Labour.”

He has reason for optimism in the face of past experience. After the Monklands affair, Helen Liddell, a former aide to the late publisher Robert Maxwell and now a Treasury minister, almost lost Smith’s safe seat to the nationalists, while in the Paisley South by-election which installed Alexander, 10,000 Labour voters stayed home. In Glasgow, two Labour councillors have in recent months defected to the SNP; Govan is seen as a prime nationalist target if Sarwar should give up the seat; and such has been the damage inflicted on Graham that even his 8,000 majority in West Renfrewshire is seen as potentially vulnerable.

These developments – plus opinion polls pointing to a 15% drift to the SNP in upcoming Scottish parliamentary elections – may herald an reinvigorated democracy. But some observers think that the sleaze sagas are a warning for the rest of Britain. The most important corruption in the west of Scotland has not been criminality or votes-for-trips, but a lack of active democracy existing in apparently democratic institutions. With colossal majorities in legislative chambers, a lack of debate on crucial issues, the perks of office jealously shared among cronies, and behind-the-scenes feuding between cliques, some now ask whether they see on Clydeside the Labour government’s eventual fate.

MORE TOPICS:

Bactrim-Septra: a secret epidemic

Research cheat Andrew Wakefield